Ever since ancient times, Europeans have held the Far East in awe, fantasizing that countries such as China, India, Indonesia and Japan were magical kingdoms filled with all kinds of wondrous, rare and amazing commodities – silk, porcelain, tea, spices, beautiful timber, rare dyes, ivory, tortoiseshell, and fascinating jewels! Trade-goods such as ivory, ginger, cinnamon and pepper were exported from China and India all the way to Europe along a network of roadways, rivers and coastal sea-routes which eventually became collectively known as the ‘Silk Road’.

Commodities transported along the Silk Road were rare, expensive, exotic…and open to theft…unscrupulous dealers…confidence artists…spoilage or damage…and all manner of mishap. Added to that the fact that products took literally months to travel from India, Indonesia, Japan or China to Western Europe, and it’s no wonder that the prices paid for these things were astronomical!

To try and keep costs down and to maximise how much they could purchase (and sell) at any one time, European traders increasingly took to shipping vast amounts of exotic goods back to Europe by sea. However, this was expensive, dangerous, and extremely time-consuming, with a round-the-world voyage taking the better part of a year, or more, to complete. Having to sail around the Cape of Good Hope, or Cape Horn, meant that sea-voyages between Europe and Asia were never going to be easy, or safe.

To try and rectify this, ever since the 1500s, and the discovery of the Americas, Europeans had set their sights on trying to find a faster, easier route to Asia – one which didn’t sail around Africa, or around South America, one which could vastly speed up trade between East and West.

What is the Northwest Passage?

The route chosen to try and improve trade between Europe and Asia was one which sailed west across the Atlantic, north, past Greenland, and then west, past the northern coasts of Canada, and then south into the Pacific.

This route became known as the Northwest Passage.

In an era when Europeans were still calling mythical continents “Terra Australis Incognitia” (“Unknown Southern Land”), nobody actually knew whether a Northwest Passage even actually existed!…What if it did? What if it didn’t?

The only way to know for sure was to physically sail to Canada, and map out the entirety of the northern Canadian coastline to find out if it was even possible to sail from the Atlantic coast of Canada to the Pacific.

Numerous expeditions had tried over the years, with little success. Even famed navigator and Royal Navy officer, James Cook, legendary for mapping most of the South Pacific – had tried – and failed – to find the Northwest Passage.

In 1837, King William IV died, and his niece, the 18-year-old Princess Victoria, ascended the British throne as Queen Victoria!

The Victorian era, as the period between 1837-1901 is known, was an age of optimism, determination, confidence, and great technological advancements! Huge progress was made in the fields of medicine, manufacturing, industry, technology and communications during this time. It was for all these reasons that, in the 1840s, Britain decided that it was time for another crack at the Northwest Passage!

Equipping the Franklin Expedition

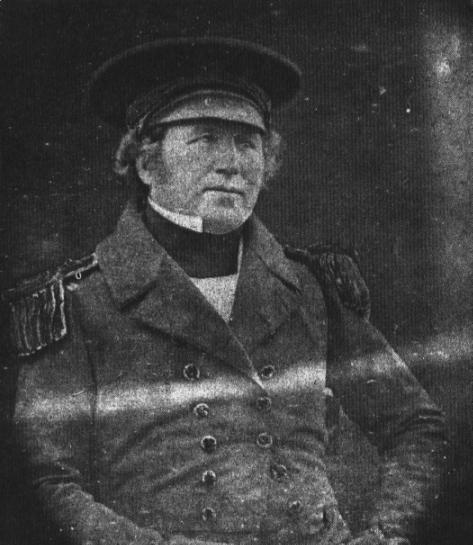

In the 1840s, the British Admiralty decided that the time was ripe for another expedition to the Northwest Passage. To lead this daring venture into the frozen north, it selected what it thought, was the best man for the job: Captain Sir John Franklin.

Born in 1786, Franklin was a man of considerable accomplishment. A veteran of the Napoleonic wars, and naval officer who fought alongside Admiral Nelson, a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, and former Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania), Franklin was used to a rough life, and spending years away from home – both of which would be vital qualities required of any leader of such a perilous expedition! Franklin was also selected for his intelligence – of all the letters after his name and title, were three which were possibly, the most impressive: FRS. Fellow of the Royal Society!

The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge – or the Royal Society, for short – is the oldest surviving, and most famous, learned society in the world. Since its establishment by royal charter by King Charles II in 1660, it has been at the forefront of scientific, technological and medical research and advancements for the past 360 years! Membership to the Royal Society is strictly by invitation ONLY, and to be invited to become a member (or more precisely, to be granted a ‘fellowship’) is not only a gigantic honour, but also confirmation of one’s vast contributions to the worlds of science and technology!

Famous fellows of the society included Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Stephen Hawking, Sir David Attenborough, Charles Darwin, and brainiac-of-brainiacs: Albert Einstein!

To gain admission to the Royal Society is so difficult that surely anybody who held the letters FRS after their name, was certainly not going to be some addlepated dunderhead, right? As if the powers-that-be needed even more convincing – Franklin had already headed a number of other expeditions to the Arctic in previous years! What else could one ask for? The Admiralty was convinced, and duly appointed Franklin to be expedition leader.

The Ships: Darkness and Terror…

With its leader selected, the next task was to find some way of getting the crew through the Arctic. The Admiralty selected two ships: The Erebus, and the Terror! Erebus is named for Erebos – Greek God of Darkness!

Two ships. Darkness, and Terror.

Sounds like a good omen!

To survive the long, likely multi-year voyage through the Arctic, the two ships were renovated or “fitted out” to be as well-built for their new task as possible. The two ships had already proved themselves capable of arctic exploration in the past – in the 1830s, both vessels had sailed in company to Antarctica with Sir James Clark Ross (after whom the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica is named), but the British Admiralty wasn’t taking any chances when it came to trying to find the mythical Northwest Passage.

To this end, the ships’ hulls were reinforced with iron plates and rivets to guard against crushing ice, striking icebergs, and slamming into rocks. The interiors were fitted out with cabins, galleys, toiletry facilities, libraries, an infirmary and physician’s offices, and the holds were modified to fit as many of the essential supplies as possible. As a further safeguard, they were also subdivided into watertight compartments, just like on later ships like the Titanic, to try and reduce the dangers of flooding if the ships were holed by ice.

On the technological side, the ships were equipped with steam engines and propellers, and even a rudimentary, steam-powered central-heating system, to keep the ships at least moderately comfortable in the freezing sub-zero temperatures that the crew were certain to encounter. To make sure that the ships weren’t rendered impotent and immovable by some sort of mechanical breakdown during the voyage, even diving suits were included in the equipment-stores, so that underwater repairs could be made.

Food and Drink for the Voyage

The Franklin Expedition was expecting to be away from civilisation for at least two to three years, during which time, they would have to survive almost entirely on whatever food they had brought with them. To this end, the ships were almost exclusively provisioned with one of the greatest wonder-products of the Victorian age!

Canned food.

Canned, and bottled food, have existed since the late 1700s. Canning started becoming really popular in the Georgian era, when Napoleon Bonaparte insisted that somebody had to come up with a convenient way of packaging large quantities of food so that it could be transported easily, stored safely, and wouldn’t spoil for weeks, months or even years at a time.

Food that was canned and sealed tight could last almost indefinitely – a useful trait for an expedition that would be away from civilisation for up to three years! Early canned food was packaged so well that the cans were nigh impossible to open! Soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars were given canned food as rations, but exactly how the hell you get into them – well – that was a matter of ingenuity! Bayonets, axes, hammers, chisels, pocketknives, and even the odd musket-round were all used to try and crack open the almost impregnable containers to gain access to the food within! Canning was almost too effective for its own good!

The task of provisioning the Erebus and Terror with the necessary rations was given to industrialist Stephen Goldner. On the 1st of April, 1845 – April Fools’ Day – an order of…wait for it…8,000 cans of various types of foodstuffs…were to be prepared in just SEVEN weeks! If this was Franklin’s idea of an April Fools’ Day prank, then Goldner was not impressed, and while he tried his best to meet the order, the need to cook, pack, lid, and solder, over a thousand cans of food a week – all done by hand, remember – led to inevitable quality-control issues. In the understandable haste, lids were improperly placed on the cans, and the lead-based solder used to ensure an airtight seal between the lid and the can itself was unevenly and sloppily applied by workers who were rushing to meet deadlines. This led to some cans being left with tiny holes and gaps in the solder, or even instances where the lead solder leaked into the food due to improper application!

Whoops…

While Goldner’s canning company provided the crew with the majority of their everyday food, for more specialised, luxury provisions – and what good Victorian exploratory expedition could be without those – the ships’ officers turned to another supplier: Fortnums!

Founded in London in 1707, Fortnum & Mason has, for over 300 years, been one of the most famous department-stores in the world. Specialising in exotic and luxury foodstuffs, Fortnum’s has been patronised by almost every great explorer in history, from Sir Edmund Hilary to Earl Carnarvon and Howard Carter – and the officers of the Franklin expedition were no exception!

Along with the food, equal attention (or perhaps, rather more attention) was paid to something which was…rather more important: What the crew would drink during the voyage. As it would be impossible to bring along enough drinking water, wine, rum, grog, brandy and scotch for a trip expected to last at least two years, the Erebus, and the Terror were fitted out with a new innovation: Desalination plants! These water-filtration systems would be able to process seawater pumped up from the ocean and onto the ships, and make it drinkable, giving the crew – in theory – an endless supply of fresh, drinkable, desalinated water!

The Crew of the Franklin Expedition

Everybody knew that going to the Great White North was going to be a perilous and possibly fatal endeavour. Because of this, the Franklin Expedition had to choose its crew with great care. In total, the two ships – Erebus and Terror, were loaded with 134 men: 24 officers, and 110 seamen and other crew.

Among the crew were four surgeons, two blacksmiths, cooks, stewards, four stokers (to handle the steam-engines), royal marines, engineers, and dozens and dozens of able seamen. Added to this were the two captains: Of the Erebus – Captain Sir John Franklin himself, and of the Terror, Captain Francis Rawdon Crozier.

The two ships were fully provisioned and equipped, crewed and loaded, and left England on the 19th of May, 1845.

The Trip to Greenland

The first leg of Franklin’s voyage was from England to Greenland. Departing as they did, on the 19th of May, the ships sailed north, first to Scotland, and thence to Greenland. During this part of the voyage, the two arctic ships were accompanied by two more ships bringing up the rear with extra supplies and equipment. When the ships arrived in Greenland, the supply ships loaded their cargoes into the two arctic ships and prepared to head for home. Unnecessary equipment, cargoes, and all outgoing mail from the two expedition ships were loaded onto these ships during the expedition’s stay in Greenland, so that they could be returned to England. Along with all the mail and other things that wouldn’t be going on this epic voyage of discovery, were five men:

Thomas Burt, an armourer (aged 22), William Aitken, a royal marine (aged 37), James Elliot, a 20-year-old sailmaker, Robert Carr (another armourer, aged 23), and an able seaman named John Brown.

The five men, one from the Erebus, and four from the Terror, were excused participation in the expedition on the grounds of health – all five men had fallen ill, although what of was not recorded. They were loaded onto the departing supply ship, and went with it when it returned to England.

They didn’t know it yet, but these five men would later count their lucky stars to be the only members of the expedition to ever return alive.

The Voyage to the Great White North

Once the ships had been re-provisioned, and all necessary supplies and shopping had been accounted for and completed, the next step in the voyage was the most perilous: entering the Arctic Ocean!

With their modern, canned provisions, central heating, steam engines, desalination plants, and even the first, rudimentary daguerreotype cameras, everybody back home in England felt that the Franklin Expedition was by far the best-equipped and most prepared crew that had ever set out to tackle the ferocity of the frozen north, and if they couldn’t find the Northwest Passage…if indeed such a passage even existed!…then nobody would!

The ships left Greenland at the height of summer, and sailed northwest, towards Canada. The aim was to reach the Arctic during the warmest months of the year, to give them as much time as possible to explore the region before the all-too-short Arctic warm season faded away, and they would be doomed to spending months trapped in the ice, waiting for the spring thaw the next year.

By the 28th of July, 1845, the ships had crossed Baffin Bay off the west coast of Greenland. It was at this point that the ships were spotted by two whalers sailing south – the Enterprise and the Prince of Wales. This would be the last time that any of the Franklin crew, or their two ships – would be spotted by European eyes. It was shortly after this that the Erebus and the Terror disappeared into the frozen, merciless embrace of the Arctic, to begin their expedition proper.

The Sea of the Midnight Sun

Exactly what happened to the remaining 129 men of the Franklin Expedition from July 28th onwards, can only ever be guessed at. Few written records remain, and what eyewitness accounts that there were (by Inuit eskimoes native to northern Canada) were initially, largely discarded as fanciful, overblown and inaccurate, by rescuers who refused to believe the truth of what had actually taken place so far from civilisation.

1845: The First Year

The Erebus and the Terror sailed in company westwards from Baffin Bay and into the frozen wastes of the Arctic Ocean. With only scant maps to guide them, and absolutely no ability to rely on compass-bearings (being so close to the North Pole, magnetic compasses were useless), the crew had to rely on the positions of the sun, stars and moon to navigate.

The Arctic summer was particularly cold that year, and progress was slow. By the time the ice started to freeze up again in the approaching winter, the two vessels had only made it as far as Cornwallis Island. Unable to go any further, Franklin and his crew made the decision to stop here for the winter. The ships were anchored off the coast of a tiny, gravely outpost sticking up out of the water – Beechey Island.

Along with being their winter camping-site, Beechey was also where the crew of the Franklin Expedition farewelled the first three of their own: John Torrington (Petty Officer), William Braine (private, Royal Marines), and John Hartnell (Able Seaman). Later autopsies on the corpses determined that the three men had died of what the Victorians called ‘Consumption’ – or tuberculosis.

1846: The Second Year

With the spring thaw, the ships started moving forward once more. It was Franklin’s job to find the fastest, safest route through the Arctic to the Pacific Ocean, and to try and achieve this, he was determined to avoid the more extreme, more northern routes that might be available to him, and instead stick to southern passages through the Arctic. After mapping Cornwallis Island, the Franklin expedition had two choices to make:

They could either sail directly west, between Melville Island to the north, and Victoria Island to the south, and out into the Arctic Ocean, or else south, between Prince-of-Wales Island and Somerset Island.

Not wishing to linger in extremely-northern latitudes for any longer than was absolutely necessary, Franklin’s crew elected to sail south, reasoning that it might be warmer, and therefore, easier to navigate. To this end, they sailed from Cornwallis Island through Peel Sound, a stretch of water between Prince-of-Wales Island to the west, and Somerset Island, to the east.

What nobody aboard the Erebus or the Terror could’ve known at the time was that they were sailing into a deathtrap.

The problem with sailing south during the spring thaw of 1846 through the Sound was that this was the exact same route that all the sheet-ice, icebergs and growlers took, when they too, broke free from other bodies of ice, and started drifting! Currents drove them south towards Canada, and Franklin’s two ships soon found themselves trapped in the mother of all arctic traffic-jams! Had they sailed west, the ice would simply have floated past them as the expedition made for the open sea past Melville Island, but by going south – the Franklin ships ended up going in the exact same direction as all the ice that they were trying so desperately to avoid! The result? The ships became stuck in ice. Again.

At first, Franklin’s crew were unphased. After all, they knew that something like this was likely to happen, and so once they had made as much forward progress as they could, they dropped anchor off King William Island on the 12th of September, 1846, and prepared to make winter camp, yet again. Not wishing to stay onboard the ships in case they broke free of the ice prematurely, or were crushed by the compacting force of more ice piling up behind them, the crew instead offloaded necessary supplies from the ships and set up camp on King William Island itself, where they would be safe from the risk of ice cracking, breaking and splitting apart if the floes and sheets shifted unexpectedly.

1847: The Third Year

By early 1847, it was time to start moving again. The spring thaw had come and while the ice did start breaking up, as it should’ve done, it wasn’t nearly as much as one might’ve expected. The ships moved at literally a glacial speed, limited entirely by the movement (or lack of movement) of the ice which surrounded them.

At the end of Peel Sound, the two ships once again reached a junction where they would have to make a decision: Sail east, around King William Island, or sail south, past the island, and then westwards past Victoria Island and continue onwards to find the Northwest Passage.

Unsure of the exact geography of King William Island, and whether or not they would be able to sail all the way around it, the ships chose to stick to their current route and sail south.

Again, it was a decision that they would come to regret. What none of them could’ve known was that by sailing east and around King William Island, they would avoid the heaviest ice-floes, popping out near the southern coast, and then sailing on past Victoria Island’s southern coastline and towards the Pacific. By sailing directly past King William Island’s western coast, however, they were headed into a virtual logjam of ice, which packed together in an immovable, frozen barrier, their movement slowed to a crawl thanks to all the small islands that bridged the gap between Victoria and King William Islands.

It was through this narrow, congested, ice-clogged channel that the two ships now had to navigate.

The men tried everything to get through the ice. Axes, sledgehammers, chisels and ice-saws were used to cleave, slice and cut through the ice, which was several inches, or even feet thick, but their efforts yielded negligible results, with the ships barely crawling forwards. In desperation, the men even resorted to using more dangerous (but also more effective) mining techniques to get through the ice!

Using augers, the men drilled shafts into the ice, and packed them with gunpowder. The powder was tamped down and fuses were lit. The explosions fractured the ice, but not nearly enough to break it into manageable chunks, once again forcing the men to expend valuable calories in shifting the tons of ice by using hand-tools.

By May, 1847, the ice remained just as immovable as ever, and it was at this point that the crews started to lose hope. With explosives running low, no coal to fire the engines, and the men exhausted from the freezing cold and backbreaking labour, morale started to plummet among the crews.

What happened next is only known thanks to a message, stored in a metal tube and hidden in a cairn (a pile of stones built up to form a pillar) that was left by the Franklin crew. Dated the 28th of May, 1847, it stated that four days previously on the 24th, a party of eight men (two officers and six men) had left the winter encampment on King William Island, and were attempting to explore and map the island. The note concluded “All Well”.

1848: The Fourth Year

Whatever the hopes of the Franklin crew might’ve been, they appeared to have vanished quickly. Just a few weeks after the note in the cairn had been written, Captain Sir John Franklin died, on the 11th of June, 1847. With the ice refusing to thaw for a second year in a row, the men remained trapped on King William Island throughout 1847 and into 1848, where the ice…AGAIN…refused to melt!

Getting desperate, the men decided that the time had come to look to their own salvation, and to abandon the mission entirely. On the 25th of April, the cairn was revisited, and the note extracted from within. An addendum was written on the few inches of remaining paper, stating that Franklin had died, and that the crew were abandoning their ships to the Arctic pack-ice. By now, twenty-four additional men had died. From 134 to begin with, minus 5, left them with 129. Minus Franklin was 128, minus 23 others, was 105 surviving crew.

Exactly what the twenty-four men (of which Franklin was one), had died of is not recorded, although later examination of the bodies revealed a mix of scurvy, tuberculosis, pneumonia, hypothermia, and lead poisoning.

Deciding that it was safer to leave the ships and head south to find civilisation, the crews took the drastic step of lowering the ships’ lifeboats onto the ice. Packing the lifeboats with all the available food, tools and other equipment that they might possibly need, the remaining 100-odd men, after consulting a few charts, made for Back River, 250 miles away, to the south. They reasoned that, if they could reach the river, then they could sail the boats south, and find help.

And so, on the 26th of April, 1848, pulling lifeboats and sledges packed with food and materiel, the 105 surviving crew started off on the journey that they hoped, would lead to their own salvation. Leaving the ships behind, they headed to King William Island, and started the agonising, freezing, painful and exhausting trek south.

With little water, freezing temperatures, snowstorms, dwindling provisions of increasingly questionable edibility, and suffering from everything from frostbite to scurvy, lead-poisoning and pneumonia, the men headed off into the frigid arctic wastes towards Back River, never to be seen again.

The Franklin Rescue Missions

Franklin’s crew had been forewarned that they should expect to spend at least two years, if not three, in the freezing north of the Canadian archipelago, and that they would not likely return home for many, many years. Everybody knew this. Franklin knew it, Crozier, his second in command, knew it, the admirality knew it, and Lady Franklin, Sir John’s wife, also knew it.

It was for this reason that two whole years passed, before any great concern was raised about what might be happening to the Franklin crew. In 1847, Lady Jane Franklin started getting worried, and began a gentle pressure on the Admiralty to send out a search party to try and find her husband.

The Admiralty, however…decided not to. They saw no need. After all, the Franklin Expedition was expected to be gone for up to three years! There was surely no need to panic! Not yet, anyway. However, not everybody shared the Admiralty’s confidence in the Franklin crew.

One of the men who didn’t was a certain fiction author and journalist, a man who was a close, personal friend of Lady Franklin – a man named Charles Dickens. Using his journal, Household Words, Dickens and Lady Franklin roused up public support for a rescue mission, and between 1848 to 1858, nearly four dozen search-and-rescue missions were launched to try and find the Lost Expedition, with Lady Franklin personally sponsoring…wait for it…SIX different expeditions to try and find her husband, or else, to discover his fate!

So…what happened to Sir John Franklin?

Franklin’s Lost Expedition

Exactly what happened to Franklin’s expedition has been a mystery for over 170 years. Nobody knows all the facts, and nobody knows all the truths. What is known is gleamed from what few scant documents and relics that could be found, and what eyewitness accounts the search-and-rescue teams could gleam from local Inuit natives. So, what did happen to the Franklin crew?

What follows is the most widely-accepted and, believed-to-be, accurate timeline of events.

April 26th, 1848. After two winters and two summers trapped in the ice, the Franklin crew decide to abandon their vessels, pack what supplies they can carry onto sledges and lifeboats, and trek south to Back River, to try and save their own skins.

The 104 remaining men drag their supplies onto King William Island, and head due south. It is freezing cold and the going is impossibly hard. There are no trees, no grass, no bushes…no vegetation of any kind. Just freezing wind and scattered limestone shale all over the place. The exhausted, hungry, starving men are struggling to heave the massive lifeboats along, stopping every few hours for rest and food, or to try and make camp.

This is what we know, according to all surviving written records. What happened next was gleamed from testimony taken from local Inuit Eskimos living in the area.

Unable to make it to the river, the men returned to the ships, deciding that it was safer to stay aboard them, rather than risk their lives out in the open. In 1849, when they felt stronger, they started out again in smaller groups, heading south once more.

With rations almost exhausted, the crew learn how to hunt seals and caribou to survive. Where possible, the Inuit assist them, either in hunting, or in butchering their kills. Each party thanks the other, using gifts of meat to repay each others’ kindnesses. The men learn how to cook their kills by starting fires using seal-blubber for fuel.

Slowly, parties of men of greater and lesser numbers, start to leave the Erebus to try and once again, make the perilous trek south.

During the winter of 1849-1850, the Inuit witness the crew performing a military-style burial ceremony. It is believed to be the funeral of Captain Franklin’s second-in-command – Captain Francis M. Crozier, officer in command of the Terror.

After this, more Inuit witnessed more crews of men still trying to head south. One group of up to forty men were witnessed dragging a boat behind them. They later speak of coming across a campsite littered with dead bodies, racked by starvation, cold and disease. Examinations of the bodies…or what’s left of them, anyway…caused the bleak prospect of cannibalism to rise to the surface…a fate later confirmed by proper autopsies.

By summer, 1850, the ice finally thaws. The remaining crew try to get the Erebus moving again, but severely weakened and ill, they almost all succumb to starvation and disease. Inuit recall boarding the ship to find the men dead in their cabins.

After this, in 1851, the Inuit locals report the existence of four more men. Accompanied by a dog, they head west. Who these men are, where they ended up, and what became of them is unknown. These men – whoever they are, and whatever became of them – are believed to be the last survivors of the Franklin Expedition.

These details, pieced together from written records, eyewitness testimonies from the Inuit, and relics and evidence recovered during the several fruitless searches for the Franklin crew, are all that are conclusively known about the fate of the men. Between buried bodies, human remains, and a single ship’s lifeboat with two corpses inside it, there was precious little to go on, and by the end of the 1850s, it was conclusively proven that the Franklin Expedition – widely believed to be the most well-prepared, well-stocked, most technologically-advanced polar expedition ever assembled – had been a horrifying, abject and abysmal failure, which tested mankind’s resolve and limits to so far beyond their breaking-points that polite, Victorian-era society scarcely dared to believe it.

Why did the Franklin Expedition Fail?

The loss of the Franklin Expedition is one of the great human tragic mysteries of the world, up there with the abandonment of the Mary Celeste, the disappearance of the Roanoke Colony, and the loss of the S.S. Waratah.

What happened? How did it happen? Why? These were the questions that Lady Franklin, the Admiralty, and the millions of people all over the world, demanded answers to, when the worst was finally revealed in the years following the exhaustive search-and-rescue efforts made in the 1850s.

So, what exactly went wrong?

The Ships

On the surface, the Erebus and the Terror looked like the ideal vessels for the Franklin Expedition. They were robust, well-built warships which had already proved themselves in arctic exploration well before they were selected as the vessels which would convey the Franklin crews to glory! The ships had been strengthened, reinforced with iron sheeting, had had central heating installed, and steam-engines with propellers and comfortable quarters prepared for the men. So, what went wrong?

Before they were used to convey Franklin and his men into the pages of history, the Erebus and the Terror had been used by Sir James C. Ross, during his explorations of Antarctica. And before that, the two vessels had been bomb ships! Bomb ships were a type of warship designed to fire mortar-rounds, instead of the conventional cannon-shot that most sailing warships would’ve used. They were literally used to bombard the enemy – hence ‘bomb ships’.

Because of this, their construction meant that they had to be very stable, to withstand the powerful recoil of the mortars going off on their decks. This meant that they were heavy, and had low centers of gravity, to reduce the risk of them capsizing and rolling over from the recoil of the mortars. This is great in battle, and even great when you’re sailing through the depths of the Southern Ocean…but it’s useless up in the Canadian archipelago! These heavy, ungainly ships with their deep drafts were unsuited for the shallow waters of the Arctic, especially when it came to weaving through the dozens of little islands immediately north of the Canadian mainland.

In the 1840s, the two ships had been converted to steam-propulsion, but crudely. Steamships did exist in the 1840s, but the engines installed on these two vessels had one great flaw – they weren’t maritime engines! Instead of purpose-built ship’s engines, the Erebus and the Terror were fitted out with small steam-locomotive engines used to power trains! Weighing up to 15 tons each, the engines were of a poor and inefficient design, and nowhere near powerful enough to generate the horsepower required to move the ships forward at any appreciable speed, or for any great distance, partially because neither were they given anywhere near enough coal! When the ships had been provisioned in England, only 120 tons each of coal, had been provided to them. At 10 tons a day, this would last just 12 days.

12 days’ worth of coal, for a voyage expected to last three years.

Because of this, the engines were almost never used. It took too long to heat them up, boil the water, create the steam and drive the engines to move the ships…and the engines weren’t nearly powerful enough, anyway. Why the Erebus and the Terror hadn’t been fitted out with proper maritime engines is unknown, but the end-result was the same: The engines, being underpowered and rarely used – were nothing but dead weight at the bottom of the ships, making already slow vessels even slower.

The Food

It’s long been believed that one of the main contributing factors to the disaster of the Franklin expedition was the food that the men ate during the voyage. The vast majority of it was canned. In theory, this was a good idea. Canned food is easy to store, easy to ration, takes up less space, is easier to cook and easier to serve.

But only if it’s done properly.

The cans of food and beverages used on the Franklin expedition were poorly sealed and the food was not properly prepared. This led to spoilage, leakage, and loss of nutritional value. The result? The men started suffering from the one disease that all seamen lived in mortal terror of: Scurvy, caused by a crippling lack of Vitamin C.

Scurvy had been the nightmare-fuel of sailors for hundreds of years, even before the Franklin expedition set out. In the 1700s, it was discovered that citrus juices could prevent scurvy, and to this end, the Royal Navy instituted a system whereby every sailor was given generous quantities of grog every day, to keep scurvy at bay. Grog was a mix of rum, watered down with lime or lemon-juice. This sweet-and-sour cocktail, a mix of booze and vitamins, kept sailors hydrated, healthy, and happy.

The canned provisions might’ve done as well, if they had been prepared properly. But apart from the lack of vitamin C, the canned food posed another great danger: Botulism. When food (especially meat) goes bad, the bacteria known as Clostridium Botulinum starts to form, which can lead to symptoms such as sight problems, speech problems and fatigue – all of which would be exacerbated by the freezing cold of the Arctic.

Navigational Issues

Another huge problem for the crew, apart from the shortcomings of their ships and the deficiencies in their provisions, was the much more unmanageable problem of dealing with navigation.

To find your way around the world in the 1840s, you needed three pieces of equipment: A sextant to tell you your latitude, or North-South position, a chronometer or clock, to tell you your longitude, or East-West position, and a compass, with which to give you your direction, or ‘heading’. Compasses are magnetic. They will always point towards the magnetic North Pole, which as we know, is populated by a fat guy in a red suit who runs the world’s largest toy factory!

The problem with magnetic compasses is that the Magnetic North Pole moves. A lot. The rotation of the Earth means that the pole is constantly shifting – more than once throughout the Earth’s history, the poles have flipped completely, and then flipped back again! In most latitudes, this isn’t an issue – the North Pole (ie: True North) is so far away that these slight variations in movement made by Magnetic North are imperceptible, and a general northerly bearing is usually sufficient to guide a ship along its route – if it needs a more accurate fix – well! – that’s what the chronometer and sextant are for!

But the problem is that the shifting poles and questionable compass readings get more and more extreme the further north or south you go. Right up in the Arctic Circle, with the pole moving all the time, the compasses get completely disoriented as they try to keep up with the shifting magnetism of the North Pole. The result?

The compasses don’t point north. They don’t, because they can’t, and they can’t, because they point to Magnetic North, which, as I said, is constantly moving. This leads to the very real problem of your compasses being completely useless. You can’t rely on them at all to point the way, and can only manage to do so by maps, stars and the position of the sun…if the sun will deign to rise, that is – in the Arctic Circle, that isn’t always guaranteed.

Along with faulty compass readings came the added strain of trying to navigate a seascape which had very few accurate charts. No complete maps of the Canadian Archipelago existed in the early 1800s, and for the first time since the search for Australia in the 1700s, mankind found itself quite literally sailing off the edge of the map.

This inability to rely on maps meant that every directional change the crew made would be a literal, and figurative – shot in the dark. They had no idea what lay ahead, or what to expect. Instead of sailing west, they sailed south. Instead of sailing east, they sailed west. Instead of trying to avoid the ice, the Erebus and the Terror found themselves trapped in endless floes which refused to melt for years on end!

Captain Sir John Franklin

The last factor which spelled doom for the Franklin Expedition was, arguably, Sir John Franklin himself. While he was an arctic veteran, a famous explorer, naval hero and man of letters who was immensely popular with the British public, and well-liked by his crew, Franklin did have a number of shortcomings that made him less than ideal for the mission at hand.

Franklin’s unsuitability as expedition-leader is borne out by the fact that he wasn’t even the Admiralty’s first choice for leader! Sir John Barrow, Second Secretary to the Admiralty, and the man in charge of finding the crew to man the expedition, had hoped to convince the elderly Sir John Ross to come out of retirement and head the expedition. Ross was a famous naval officer and arctic explorer of note, but he was already approaching old age, and had no desire to go to sea – especially on such a risky mission as this!

Barrow’s second choice was Sir James Clark Ross – Sir John’s equally-famous and well-accomplished nephew, another famous polar explorer! Unfortunately, Sir James had just gotten married, and, like his uncle, had no desire to go gallivanting off around the world at such short notice!…especially when he had far more interesting diversions waiting for him at home.

Barrow’s THIRD choice for commander was an Irishman named Francis Rawdon Crozier – another polar-exploration veteran of note. While Crozier was experienced, Barrow wanted an Englishman to head the expedition, and since his first two choices had bowed out and his third was not ideal, he finally settled on Sir John Franklin – Option #4!…Ouch!

At 59, Franklin was already approaching old-age by Victorian standards. While he was a naval officer, and a polar explorer, and certainly had the intelligence to get himself admitted to the prestigious Royal Society, Franklin had many shortcomings as well. Although he was a popular hero, and was well-liked by the men under his command, whom he treated with kindness, consideration and respect, the fact of the matter was that Franklin was stubborn, hotheaded, took unnecessary risks, and didn’t always respond positively to well-meaning advice.

All these faults led to his near-death in 1819, when he attempted an overland expedition from Canada to the Canadian Archipelago, to find the Northwest Passage by land. His foolhardiness and inattention led to eleven of his 20-man crew dying of cold and starvation. By the time they abandoned the mission and his men had convinced Franklin to turn back, the remaining men were close to death themselves. Franklin survived by literally cutting up and eating the leather uppers on his hiking boots! This humiliating end to what was supposed to be glorious victory of exploration, led to him being mercilessly lampooned as the “man who ate his own shoes”!

All these issues – the failings of the ships, the problems with the food, and nutrition and health of the crew, and the navigational challenges and uncertainties faced by the navigators aboard the two ships are what led to what was supposed to be the most well-equipped polar expedition in history, going down as one of the greatest exploratory failures of the Victorian era.

In the end, the first successful maritime navigation of the Northwest Passage took place in 1906 under the command of Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen. Unlike Franklin, Amundsen had the good sense to turn EAST when he reached King William Island instead of continuing south – and that made all the difference. By turning east, he was able to sail around the island and pop out the bottom. All the tiny islands north of him (through which the Franklin Expedition had attempted to sail) now worked in Amundsen’s favour, instead of against him, like with Franklin. The islands which formed the bottleneck of icebergs and field-ice that had so impeded the Franklin expedition, kept the waterways past Victoria Island relatively ice-free, allowing Amundsen a clear passage westwards towards the Pacific Ocean!

What Happened to Erebus and Terror?

Everything I’ve written about thusfar, has just about covered the various fates of the crew, but what about the ships that they left behind? The Erebus and the Terror. What happened to them?

Again, the only way to be sure of anything, is to go by Inuit testimony. The ships were known to be above ice throughout the 1840s, but by the early 1850s, were starting to fall victim to the crushing ice that had by now, surrounded them for years. The Terror succumbed first – carried south by the crushing ice, the ship finally broke apart and sank off the southwest coast of King William Island in an area now known as Terror Bay in honour of the lost ship.

The Erebus was marginally more successful – the pack-ice had drawn the ship south along with its sister-ship, but instead of crushing the ship to matchsticks, the ice thawed enough for it to start moving again, although it did not get very far.

In 2014 and 2016, the wrecks of the Erebus and the Terror (in that order) were discovered by Canadian maritime explorers. To protect their historical integrity, the exact location of the wrecks was (and still is) a closely guarded secret, so as to prevent recreational divers from attempting to find them. The British Government, the official owner of the two shipwrecks, gifted them to the Canadian government, which later entrusted the safekeeping and guarding of the wrecks to the Inuit people, through whose territory the two ships had tried to sail, all those years ago. Among the artifacts raised from the ships was the bell of the Erebus.

The President and the Expedition

The Lost Expedition of Sir John Franklin, and their noble quest to find the Northwest Passage, happened back in 1845, over 170 years ago, and yet, in the 21st century, one particularly poignant reminder of the expedition’s great peril remains with us still. It’s likely that you’ve seen it on TV. Several times, in fact. It’s likely that you’ve seen it in photographs, on the internet, on Youtube, in TV shows, and even in big-name Hollywood movies!

Even if it wasn’t what it is, it would still be an immensely famous artifact, and yet, this irreplaceable piece of history is quite literally overlooked, every single day, without most people realising even in the slightest – what it actually is.

What is this artifact, you ask?

The desk of the president of the United States of America.

Gifted to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880 by Queen Victoria as a token of goodwill between the two nations of America and the United Kingdom, the desk – popularly known as the “Resolute Desk”, was made from the timbers of the British warship HMS Resolute, when it was broken up in the 1870s. The desk is one of three that were commissioned by Queen Victoria when the ship was finally scrapped. The other two are the “Grinnell Desk”, and a smaller ladies’ writing-desk, made for the queen herself.

The Resolute was one of the several ships which in the 1850s, sailed to the Arctic to try and find Franklin’s Lost Expedition. Had it not been for much better planning, the crew of the Resolute could’ve joined the crew of the Erebus and the Terror in their icy fate! When the Resolute got stuck in the ice, the crew decided to abandon ship, and sought refuge on an accompanying vessel which sailed them back to safety. Fearing that their ship would, like the Franklin ships, be crushed into matchsticks by the tons of ice and then sunk, they never expected to see it again. However, to everybody’s amazement, the ship broke free of the ice in the spring thaw, and drifted around the North Atlantic for years, before it was discovered by American whaling ships and sailed back to America.

The ship was restored to full working condition, with replacement rigging, sails and flags, and was returned to the Royal Navy as a gesture of goodwill between the United States and the United Kingdom. Years later, the gesture was reciprocated in the giving of the Resolute Desk – which to this day, still bears a plaque on it detailing its role in the Franklin expedition.

Want to Read More?

For the sake of brevity, I haven’t covered everything about the Franklin Expedition in detail. If you want to find out more, here’s the sources I used…

http://maps.canadiangeographic.ca/franklin-search-timeline/franklin-search-timeline.asp

“The Search for the Northwest Passage” (Pt 1)