Fire. One of man’s greatest creations. It allowed for light, heat, and the invention of the barbeque! For millenia, fire was essential to survival in one form or another. But fire was, and remains, a constant threat. Handled properly and safely, fire provided light, heat and the ability to cook delicious meals. But an act of carelessness or a lack of foresight could turn one of the most important forces known to man, into a destructive cataclysm far beyond our control.

To prevent and to manage events of the latter nature, we have firefighters, and firefighting equipment. Fire-fighters have been around ever since Ancient Rome, and they have a long and fascinating history, which this posting will explore.

Ancient Firefighting

Firemen have existed for centuries, in one form or another. There are fire-fighting teams that go back to Ancient Egypt and even Ancient Rome.

The first fire-fighting brigade of significance was established in Rome, by a man named Marcus Licinius Crassus. A wealthy businessman, Crassus employed a team of 500 men whose job it was to extinguish structural fires in the city of Rome…for a fee…to be paid…before the firefighters would even tip so much as a thimble of water…

So much for that.

The Emperor Augustus liked the idea of Rome having a firefighting force. He established the world’s first professional fire-brigade. Called the Vigiles, these men patrolled the streets at night. Upon the alarm of fire, they formed bucket-brigades and teams of laddermen and hook-men, who extinguished fires, or pulled buildings down, to prevent the fire from spreading to other structures in the surrounding areas. The Vigiles did double-duty as an early-form of police-force as well, keeping an eye out for crime, and making sure that the city was safe from both fire and thieves and generally, being vigilant. Yes, that’s where the word comes from. It’s also where we get the term “Vigilante”.

Ancient Firefighting Tools

For centuries, up until the 1800s, firefighting equipment was rudimentary. Buckets of water, long fire-hooks, to pull down buildings, ladders to reach high windows, primative hand-powered water-pumps and only moderately effective “Water-Squirts” (a handheld water-dispenser which was a bit like a modern child’s water-gun), were the main tools of the trade. Fighting a fire was less to do about putting the fire out, and more about preventing its spread. Fire-hooks were used to pull down burning buildings in danger of collapse, or to destroy buildings in the fire’s path, to create a firebreak which the flames couldn’t jump, thus containing its destructive force.

During the medieval period, firefighting was largely self-organised. Various European monarchs (such as Louis IX of France), set up state-funded fire-fighters, but also encouraged regular citizens to form their own “fire-bands”. These acted like Neighbourhood Watch committees, which patrolled the streets at night, keeping an eye out for fires and crimes in progress.

The Great Fire of London and Advances in Technology

In 1666, the ancient city of London was razed to the ground by a fire started by the King’s baker, the unfortunate Mr. Thomas Farynor. The Great Fire was a disaster unprecedented in the history of London. Sure, there had been fires before, but no fire had ever burnt down 4/5 of the city! The Great Fire of London also instituted the start of a newfangled concept in the world…insurance! For the first time ever, you could now pay for fire-insurance! An insurance-company would open an account and upon consideration of a few pounds each year, you would have fire-protection in the event of your property going up in flames. In return for your patronage, the insurance-company gave you a big, fancy metal “Fire-Mark”. This plaque was to be affixed to your residence in a prominent place (such as next to the front door), to indicate to the company’s private fire-brigade, that you were a paying customer who they were expected to help, in the event of a house-fire. And now, fighting fires was slowly getting easier, too!

By this time, the first really successful fire-pumps had been developed. They were heavy, lumbering things that needed a horse to pull them, but they did work. Their main issue, however, was that they had a very short range. You had to be right in front of the fire for the pump to be any good at all.

These early pumps were called ‘force-pumps’. This meant that water filled a piston-shaft, and the piston forced the water up a pipe and out of a nozzle on each down-stroke. On the up-stroke, the piston-shaft was again filled with water from the tank, and again, forced out by the down-stroke.

These pumps were ineffective and rather time-wasting. The man who improved them was a German inventor named Hans Haustch. He developed a suction-and-force pump in the 1600s. This meant that pumping the handle up and down both pumped out water from the piston-shaft, but also pulled more water in from the tank, creating a constant and more powerful flow of water.

Although it was an improvement, this new double-action pump was useless, relatively speaking, until the intervention of Dutchman, Jan Van Der Heyden.

van der Heyden (1637-1712), developed the one crucial bit of equipment so vital to firefighting that centuries later and every fire-station on earth still has one!…in fact, every fire-station probably has dozens of these things!

The fire-hose.

Jan van der Heyden was a Dutch inventor. He developed his newfangled ‘fire-hose’ in the 1660s. His brother Nicolaes was a hydraulic engineer…a handy person to have when designing fire-fighting equipement…and together, they developed a perfected version of the fire-hose in 1672.

Affixed to the spouts of the new double-action water-pumps, the van der Heyden Brothers’ new fire-hoses (made of leather, the only material sufficiently strong enough to cope with the pressure), allowed people for the first time to have directional, pressurised water as a means for attacking a fire. No longer was the range of your attack limited by how far you could throw a bucket or how close you could park the fire-engine, but rather, by how fast you could pump the handle. Everything else was managed by the hose. Direction, height, distance…all you had to do was point and shoot. A great improvement from standing six feet from a blazing building holding a piddly bucket of water. Despite these advances, however, in Colonial America, it was still the law in many towns that every household kept a bucket of water outside the front door at night, as a safeguard against fires. The buckets were used by the local fire-watch, and would be returned to the home-owner once the fire had been put out.

The Development of the Fire Engine

The first fire-engines, with the new water-pumps and leather hoses, hooks and ladders, axes and buckets, were developed in the 1700s. By the Georgian era, firefighting had developed to a point that it was finally practical to make a mobile firefighting unit, the fire ENGINE.

The fire-engine had been in development in the 1600s, but the first really successful versions took root at the dawn of the 18th century. Horse-drawn fire-wagons could now to be directed to any part of a city with its supply of water, hose, pump, men and equipment, to tackle a major conflagration.

It was around this time that the first modern firefighting brigades were developed. While there were still penny-pinching, profiteering private fire-companies around (they were particularly notorious in the United States), city and state governments were now establishing the first paid fire-fighters.

The first city to have such a fire-brigade was Paris. Created by order of King Louis XIV, the “Company of Pump Guards“, as it was called, was the first professional, state-funded, uniformed fire-brigade in the world.

To prevent the squabbling and fighting that had attended the Ancient Roman firefighters, and even the colonial firefighters and private firefighters in the United States, the French Government decreed that ALL firefighting missions were provided by the city, to the victim, FREE OF CHARGE.

As the 1700s progressed into the 1800s, more and more city-funded fire-brigades were established. Big cities such as London, Edinburgh and New York soon had city fire-services and organised firefighting had become a reality.

Fire-Trucks

Fire-trucks are famous aren’t they? Jangling bells, wailing sirens, flashing lights, and that distinctive “fire-engine red” paintjob!

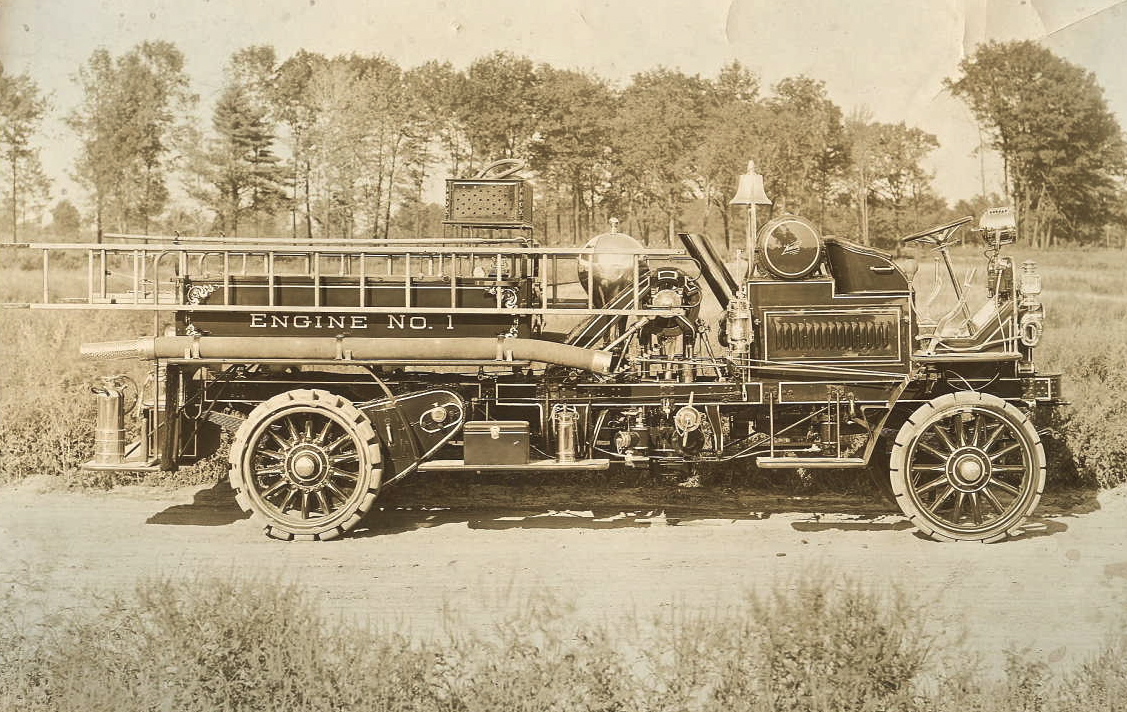

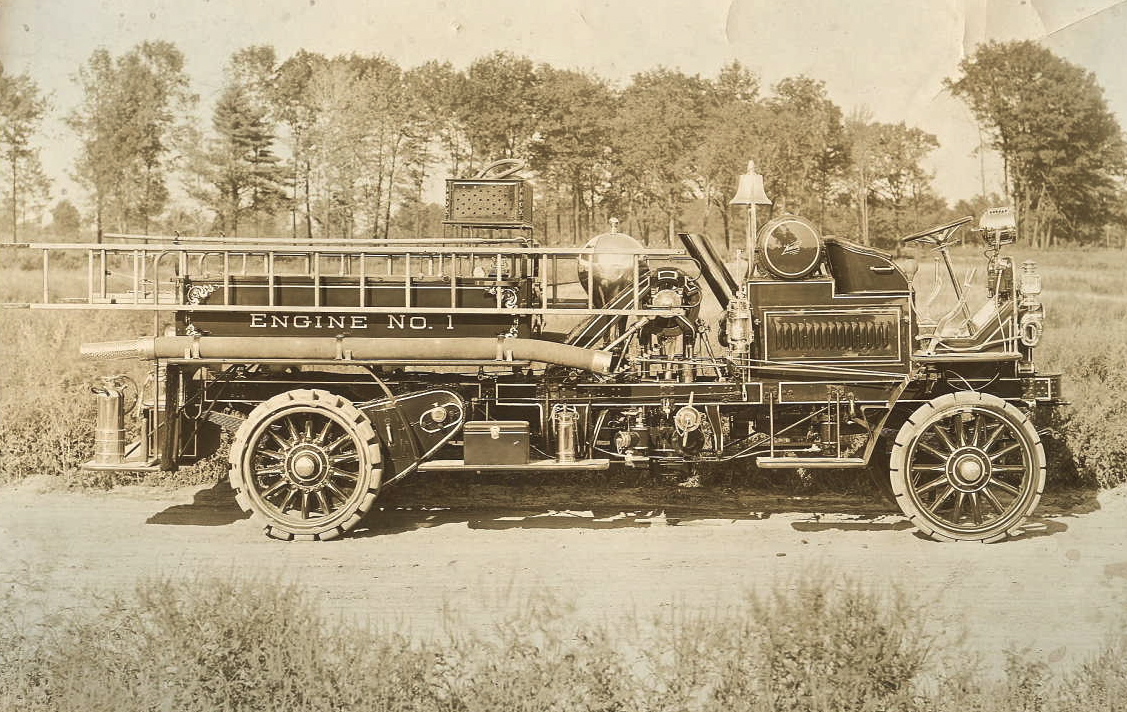

The first-ever modern fire-truck came out in the early 1900s, and belonged to the Springfield Fire Department in Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. Here’s a photograph of it:

This fire-truck was made ca. 1905, an age when most motorised vehicles were still the handmade, and extremely expensive preserve of the upper classes. But it is, nonetheless, the world’s first modern fire-truck.

Victorian-era Firefighting

The 1800s saw a huge rise in urban populations, industry, and…fire. By now, most big cities had their own, state-funded fire-services. But technology was still rather primitive. To improve firefighting, a number of changes had to be made.

Fire-wagons were still horse-drawn, but to improve efficiency, the first coal-fired, steam-powered water-pumps were installed on fire-engines in the 1800s. These allowed for longer fire-fighting times, and for more men to be used fighting the fire, rather than manning the pump.

It was around this time that the fire-dog became famous.

Dalmatian dogs are a common symbol of fire-stations in the United States. They’re famous for being white with black spots, for wearing classic red fire-helmets and for rescuing people from burning buildings!

But why are they there in the first place?

Fire-dogs, the Dalmatian dogs which are so strongly associated with firehouses, are descendant from 18th and 19th century “carriage dogs”. Carriage dogs (an ancestor of the modern Dalmatian) were the canine companions of coachmen back in the days of horse-drawn carriages. They were a sort of car-alarm with fur.

In the 17 and 1800s, when nearly all transport was horse-drawn, the welfare of the horse that did the drawing was extremely important. Especially when the transport happened to be a fire-engine. To protect horses from harm, such as horse-thieves, it was common for stable-boys, grooms and coachmen to keep dogs near to the horses, to drive away people intending the animals harm.

When a fire-engine went out on a call, the dogs went along with it, again, to guard the horses against people who might want to steal or harm the horses, which in the 1800s, were valuable assets.

The 1900s saw the end of the horse-drawn carriage, but the Dalmatian dog remained. They don’t run alongside, or guard the wheels of modern fire-trucks anymore, but they have stayed a symbol of firefighting ever since.

Fire Extinguishers

For most of history, the most widespread fire-extinguisher of any kind was a bucket of water stored next to the stove, or on the front porch.

The first modern fire extinguishers were developed in the 1800s.

Capt. George William Manby, a writer and inventor from England, created the first modern fire extinguisher in 1813.

It was designed to be portable, but it was made of copper, and weighed about 12kg! But it was, nonetheless, a fire-extinguisher.

It was filled with a water-and-potassium-carbonate solution, contained under pressure. In the event of a fire, the pressurized solution could be sprayed out of the nozzle to extinguish the blaze.

In the second half of the 1800s, numerous inventors came up with extinguishers which did more than just spray ordinary water onto a fire. Starting in the 1860s, inventors created the “soda-acid” fire extinguisher, which was particularly useful for fires where there might be poisonous chemicals around.

The soda-acid extinguisher worked by having the main canister of the extinguisher filled with a mix of water, and sodium bicarbonate…baking-soda!…and a separate phial filled with sulphuric acid, sealed inside the main canister, along with the water-soda mixture.

In the event of a fire, the extinguisher (depending on the design) was either tipped upside down, or a plunger was pushed or pulled. The idea was that this motion would break the glass phial inside the extinguisher. This released the acid into the water-soda mixture. The resultant reaction created high pressure, and a lot of carbon-dioxide gas. This could be forced out of the nozzle of the extinguisher to put out the fire.

One of the more interesting types of fire-extinguishers developed during the 19th and early 20th centuries was the so-called “fire-grenade”.

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher

The fire “grenade” was a sphere of glass filled with either salt-water, or the chemical carbon tetra-chloride (“C-T-C”).

Fire-grenades could be used by firemen or people in distress, to put out a fire from a distance. One simply lined up the fire in one’s sight, and threw the grenade at its base. The glass shattered and the spreading water (or chemicals, as the case might be) put out the fire, with minimal risk to the firefighter or person in distress.

In some places, fire-grenades were placed on special hair-trigger harnesses above doorways in big, public buildings. This way, if there was a fire, the grenades could fall from their harnesses into the doorways above which they were installed. This kept the doorway clear of flames, allowing people a safe escape-route (so long as you were fine with running on top of broken glass!).

Fire-Helmet

Ah, the classic fire-helmet. Originally made of leather, or brass, and today more commonly made of special plastics, the fire-helmet was developed during the Victorian era, as a way of protecting firemen from two of the biggest dangers of fighting a fire: Collapsing buildings, and getting soaked.

Fire-helmets are famous for their long, sloping rear brims. These are designed to protect the neck and the back of the head, and to deflect falling water away from a fireman’s neck, and going down the back of his shirt. Meanwhile, the iconic shape is designed to protect against falling objects, such as collapsing scaffolding, bricks and other debris that might come crashing down out of a fire-weakened building.

Brass helmets were popular during the Victorian era. But they started being changed for safer plastic helmets in the 1900s because of the risk of electrocution from electrical fires. As a result, fire-helmets today are made of special, heat-resistant plastics and composite materials.

Fire Hydrants

The first ‘fire hydrants’ of a sort, were developed in the 1600s. Cities lucky enough to have running water had it transported around town in wooden mains-pipes, which were buried under the streets. In the event of a fire, firemen would dig a hole in the street to expose the water-mains below. A hand-drill was used to bore a hole into the pipe. As the water rushed out and filled the hole around the pipe, a bucket-line could be formed around the hole, filling buckets with water and sending them, hand-over-hand, to the blaze.

When the fire was extinguished, the hole in the mains pipe was plugged with a wooden bung. The hole in the street was filled in, and a marker was placed on the spot. This was so that any future firefighters would be alerted to the presence of a previous bore-hole in the area, if they ever needed to fight a fire in that street again. This is why some people still call fire-hydrants ‘plugs’ to this day; because they literally plugged the water-mains.

The modern fire-hydrant, which we see on street-corners, and which are painted bright red, came around in the 1800s. It was invented in 1801 by Frederick Graff, then chief-engineer of the Philadelphia Water Works. Ironically, the patent-papers for Graff’s invention were lost when the United States Patent Office in Washington D.C. burnt down in 1836!

The Firepole

It’s a scene played out in old movies, cartoons, T.V. shows, and in almost every episode of “Fireman Sam“; the call comes in, the alarm-bells start ringing, and firemen leap into action, jumping for the fireman’s pole, swinging around and sliding down the shaft to the ground floor of the firehouse, to jump into their uniforms, put on their helmets, start up the fire-truck and charge off to the scene of some catastrophe, red lights and sirens glaring and blaring.

The fire-pole was invented in Chicago in the 1870s. As with many inventions, necessity, and a certain level of ingenuity, gave birth to one of the most iconic pieces of firefighting equipment ever.

Firehouse No. 21 in Chicago was an all-black firehouse, and the resident captain, David Kenyon, was stupefied when he saw one of his firemen, George Reid, slide down a pole from the second storey of their three-storey firehouse to the ground floor to respond to an emergency.

At the time, fire-poles did not exist; Reid had actually used the lashing-pole which the firehouse used in transporting bales of hay for the fire-wagon horses. The pole was used as a securing-point when hay-bales were loaded onto the hay-wagon, to stop them rolling off during their deliveries.

Kenyon was so impressed that he pestered the Chicago fire-chief over and over and over again to give him permission to install a similar, purpose-built pole in his firehouse. Eventually, the chief gave in, and agreed – provided that the funds needed for the installation and maintenance of the pole came entirely out of the pockets of the firemen who used it.

And so it came to be, that in 1878, the world’s first fireman’s pole was installed at Chicago Firehouse No. 21.

At first, nobody paid any attention to the pole, and other firemen thought it was stupid and ludicrous. It was some ridiculous toy to play around with when the boys at firehouse 21 had nothing else to do!

But other firehouses began to sit up and take notice when they realised that Firehouse 21 was responding to emergencies much faster, especially at night.

Not having to deal with doors, staircases, landings and overcrowded corridors meant that the firemen could literally slide into action and be ready to go in just a few minutes; compared to having to run down stairs, hold doors open, and risk tripping and falling over, especially in the dark.

With the benefits of fire-poles established, every firehouse in the world began to be fitted with them. To make them stronger and longer-lasting, the world’s first metal fire-pole (made of brass), was installed in Boston, in 1880.

An old fire-pole with important safety-features:

An old fire-pole with important safety-features:

Double trap-doors, and a safety-cage

These days, fire-poles are sometimes considered more of a hindrance than a help, because of the dangers of sprained or broken legs and ankles, and risks of losing one’s grip, and falling. Some countries have outlawed them altogether, but other countries continue to use them, albeit, with better safety-measures in-place, such as protective railings, and padded landing-mats. These prevent accidental falls, and cushion any hard landings.

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher

An antique glass ‘grenade’ fire-extinguisher An old fire-pole with important safety-features:

An old fire-pole with important safety-features: