With the anniversary of D-Day coming up, this article is written to commemorate the original and most famous of all D-Days…the sixth of June, 1944.

The Second World War is famous for a lot of reasons. It was the most expensive war, it was the costliest war in human lives, it had the weirdest national leaders at the helm at the time (a paraplegic Yank, a chainsmoking, paintbrush-brandishing MP, a mustachioed Russian lunatic and a crazy Austrian guy with a toothbrush moustache and half his sexual equipment hanging around beneath him)…but the Second World War also holds the record of being the war with the biggest ever seaborne invasion. No, not the Battle of Dunkirk…that was the biggest seaborne evacuation; but the Battle of Normandy, specifically, the naval landings on the beaches of France.

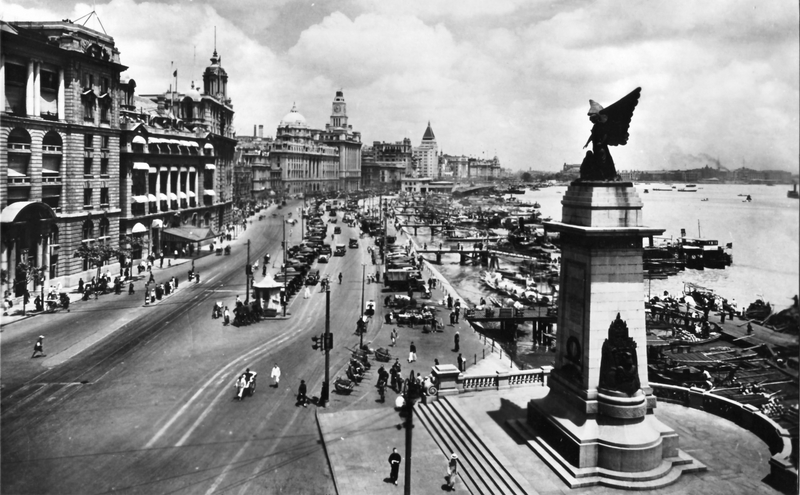

The Allied attempt to liberate northern France and to start the process of beating back the Germans and driving them out of lands which were not their own was codenamed “Operation Overlord”. However, the actual beach-landings were given the codename “Operation Neptune”. It was during Operation Neptune that all those famous photographs were taken…like this one:

Seaborne Invasions

In warfare, invasions by sea have always been the most difficult to pull off. Airborne invasions involve planes strafing and bombing the target-area and then sending in paratroopers. Land-invasions are done using infantry and tanks, possibly with air-support. In both instances, getting onto dry, solid ground is pretty easy. Either you’re already there…or you soon will be.

Seaborne invasions, however, have always been tricky. A soldier sloshing through the surf with his uniform, his rifle, his ammunition, his helmet, his kit, his boots and other necessities was liable to be bogged down in the soft, shifting sand beneath the waves. This makes him a sitting duck for any defending soldiers, who can stick out their rifles and shoot him. Added to this is the problem that to get the attacking soldiers near to the beach, you need small boats. Small boats that are fast, light and which can go right up to the sand without running aground. Prior to the Second World War…no such boats existed! From the time of Napoleon right up to WWI, warships were forced to use regular wooden ship’s rowboats to ferry their troops ashore. This was slow, dangerous and catastrophic. Because these boats couldn’t go right up onto the beach, soldiers had to jump over the sides of the boats and wade through water that could be up to their waists, to get to the sand! This wasted time and made the men easy targets for enemy soldiers on land.

Operations Covered in This Article

In my mind, and probably in the minds of thousands of others…It is a great mistake to call the invasion of Normandy a single battle or operation. It sure as hell was not. The Invasion of Normandy was a concerted effort by thousands of people doing dozens of tiny little things and a few big things to pull off the most audacious and ridiculous and fantastic beach-assault in history. Covered in this article will be the following ‘Operations’ that made up the various elements of the Normandy Invasion.

Operation Overlord – The Battle of Normandy.

Operation Neptune – The Storming of the Beaches (more famously known as “D-Day”)

Operation Mulberry – The creation of a floating harbour off the coast of France.

Operation Cobra – The breakout from the beachhead to commence the liberation of Europe and the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Specialised Invasion Equipment

Folks fighting the Second World War realised pretty quickly that if they intended to win the war by an invasion of Europe by sea, they would need a lot of specialised fighting equipment with which to do it. What kinds of mechanical curiosities did people whip up to put an axe to the axis back in the 1940s?

Higgins Boats

The Higgins boat…which is the more people-friendly name of the water-craft also known as the “LCVP” (Landing Craft: Vehicles & Personnel), was one of the most famous and vital inventions of the Second World War, without which, the large-scale naval invasions such as those in Italy and France, would not have been possible.

The Higgins Boat was invented by an American chap named Andrew Higgins. The problem at the time was that since conventional boats needed keels to slice through the water, they were not able to get right up onto the beach during naval assaults: The keel would dig into the sand and strand the boat out in the surf, unable to move inland any further. To combat this, Higgins created a flat-bottomed boat which he based on the boats then used in navigating swamps and marshes in the United States. Having a flat bottom meant that his craft could go right up onto the beach and not get bogged in the surf.

Although referred to as ‘Higgins boats’ in this article for reasons of simplicity, they went by a variety of names. One of them was the ‘LCVP’ (Landing Craft: Vehicles & Personnel)

The other feature of the Higgins boat was its famous ramp-front. Another problem of the time was getting soldiers out of their boats as quickly as possible. Because of their high sides, it was hard for soldiers to get out of regular row-boats quickly enough, and this meant that they could be killed easily by enemy gunfire. Having a boat with a ramp that dropped down meant that soldiers could run right off the boat, onto the beach and find cover. The ramp also allowed vehicles such as Jeeps, small, wheeled artillery pieces and small tanks, to be driven right off the boats and onto the beach.

Higgins was quick to see the necessity for his new invention. Production of them started in 1941! Higgins boats were not fast (12kt), not pretty and certainly not comfortable (with the flat bottom, the Higgins boat bellyflopped across the waves with all the grace of a seal), but it was important! The war would not have been won without it, and Normandy would’ve been a disaster.

D-D Tanks

Duplex Drive tanks (shortened to ‘DD Tanks’ or jokingly…Donald Duck tanks) were the Allies’ solution to getting tanks and the necessary firepower and speed that they brought with them…onto the beaches of Normandy as fast as possible.

DD tanks were invented in the early 1940s. The Allies knew that it would be asking too much if they kindly asked the Wehrmarcht if they might, pretty-please, park a few of their tanks on the shores of France for them to use when they came ashore and blasted through their defenses. Instead, they needed to find a way to get their own tanks to France. The problem was, to get tanks onto land, the Allies would need a harbour. But to get a harbour, they first had to capture it. And to capture it, they needed tanks, but to get tanks, they needed a harbour and…you get the idea.

To get tanks ashore without a harbour, the Allies decided to create a floating tank (hence the alternate name ‘Donald Duck tank’). The tanks floated thanks to inflatable screens which were placed around them, and were propelled thanks to rather weak (though effective) outboard motors. The inflatable and collapsable screens, used to give the tanks the necessary boyancy so that they could float ashore, were made of waterproofed canvas. The tanks were offloaded from warships and were then sailed towards the beaches. Once the tanks reached the beaches, the inflatable screens were deflated. They collasped around the sides of the tank, giving the tank-crews the ability to just drive ahead and blast the hell out of the enemy.

“Ducks”

Officially called the ‘DUKW’ (utility vehicle with all-wheel drive designed in 1942), the ‘Duck’ as it was affectionately called, was one of the most important machines invented for the Invasion of Normandy. Based off of an ordinary truck which had its body removed from its chassis to be replaced by a watertight, boat-shaped hull, the ‘Duck’ was an amphibious delivery vehicle, able to power itself through the water and drive out of the surf onto the beach. These floating pickup-trucks were essential to the Nornandy invasion in that they were able to ferry cargo from ships docked at sea, to land-forces fighting on the beaches and then go straight back out into the water again. Twenty-one thousand ‘Ducks’ were manufactured during the War.

Hobart’s Funnies

The Allies had been planning to charge into Normandy for years…and the Axis knew that the Allies were going to come charging in. The only thing was, the Axis didn’t know where the Allies would come ashore. Because of this, the Axis barricaded, reinforced, booby-trapped and built up every single square yard of sand which made up the French coastline, to impede the Allied advance. To break through the multiple layers of defences, from sea-mines to hedgehogs to barbed wire, machine-gun nests, defensive bunkers, sea-walls and barbed wire, the Allies knew that they needed tanks. But not just any kinds of tanks. They needed tanks that could do a variety of tasks – Tanks that could blow holes in stuff, tanks that could clear minefields, tanks that could cross trenches and ditches, tanks that could clear away the rubble of the stuff that other tanks blew up!

The number of tanks that were developed were phenomenal. And the Allies had to know how to operate every single one of them. The man responsible for gathering the armour and firepower, and whose duty it was to train the tank-crews who would use them, was Sir Percy Hobart. Hobart was a military engineer and an armoured-warfare expert, the perfect man to teach the Brits how to use their newest playthings. Because the tanks were just so weird, soldiers named the tanks after the man who taught them how to use them, and they became collectively known as “Hobart’s Funnies”.

The number of tanks that the British Army developed was phenomenal. Here’s a few of the more famous tanks and what they could do…

The Crocodile.

The Crocodile. The trailer behind the tank carried the 400gal of fuel that allowed this beast to breathe fire!

Awesome name, huh? The Crocodile was modified so that instead of a central, main gun (like what most tanks have), it had a massive, fire-belching flamethrower on the front! How cool is that!? Fed from a tank that held four hundred gallons of petrol, the Crocodile could shoot flames a hundred and twenty yards! Although somewhat inaccurate and hard to aim, the Crocodile scared the daylights out of the Krauts and was excellent at roasting the enemy alive inside the confined spaces of German machine-gun bunkers.

AVRE.

ARMOURED VEHICLE, ROYAL ENGINEERS. Not very interesting. Or is it? The AVRE, like all the other tanks, was modified for a specific purpose. This one fired huge mortar-rounds at anything that the Allies considered an impediment to their progress across Germany, namely roadblocks, buildings or bunkers. The AVRE fired massive, high-explosive shells from its main gun, capable of blowing the shit out of whatever it touched.

ARK.

Armoured Ramp Carrier. A special tank that carried a pair of ramps on its roof. It was designed to act as a bridge on wheels. If the army approached an obstacle such as a trench, the ARK would drive ahead, deploy its ramps and then park itself there and let other tanks drive over the top of it!

Crab

The crab…probably given that name because of the two arms that stuck out in front of it…was the British Army’s minesweeping and mine-clearing tank. It had two metal arms that stuck out in front of it with a long, metal cylinder between them. Attached to the cylinder was a series of chains. At the flip of a switch, the cylinder spun around and the chains whirled out in front, whipping up the ground as the tank drove ahead. The chains would strike and detonate any mines which were in the tank’s path, and provide a safe route for soldiers to follow behind.

German Beach-Defences

In the truest spirit of German efficiency, the Krauts were not just sitting around twiddling their thumbs, wondering what the Yanks and the Limeys and the Frogs were getting up to. They knew something was going to happen. They knew that an invasion of France…ONE DAY…was going to be inevitable. To shore themselves up against this inevitablity, the Germans built an enormous collection of fortifications along the northern shores of Europe, stretching alongside the English Channel and up past the North Sea. Officially called the “Atlantic Wall”, this series of defences comprised of everything from powerful anti-tank mines, miles of barbed wire, huge pillboxes and machine-gun nests, anti-tank ditches, long-range artillery cannons (set several hundred yards back, which would fire down on the landing-beaches), mines on stakes that they drove into the sand, designed to go off if a landing-craft hit it, blowing the boat and its passengers to pieces and most famously of all…these things:

Those square-looking spikey things are synonymous with beach-warfare. They’re called Czech Hedgehogs (or simply ‘hedgehogs’) and they’re an anti-tank obstacle. Incredibly easy to make and nigh unshiftable. They’re three lengths of steel beam riveted or welded together in a rough cross-shape and then just scattered all over the beach. Cheap, simple and effective. The problem with them is that if you drove a tank into one…you couldn’t crush it, and because it had no actual base, you couldn’t topple it over and just shove it out of your way. To the troops storming the beaches of Normandy, Czech hedgehogs were a mix of frustration and lifesaver all in one. They might have been a pain in the ass for the tank-crews who couldn’t drive over them or shove them out of the way, but to the infantry they were lifesavers in disguise. Allied soldiers would hide behind them and use them for cover while they fired on German machine-gun nests with their submachine-guns and rifles. They were lucky that the hedgehogs were there, for there was precious little else on the beaches that would have given them sufficient cover from the powerful counterfire of the German MG-42 belt-fed machine-gun.

The Battle of Normandy

The Guiness Book of World Records, once a noble institution of fact and intelligence, now sadly degenerated into a compendium of useless information such as who created the world’s biggest ice-cream pyramid…says that the Battle of Normandy holds the record of being the biggest ever seaborne invasion. And it’s right. Take a look at these numbers:

Planes: 12,000.

Ships: 7,000.

Troops: 160,000.

All these men and machines took part in the initial assault on the beaches on the 6th of June, 1944. And they won! But not without a lot of problems, first.

The order of battle was pretty simple – Planes go overhead, drop off surprise-packages for the Germans, ships come, deploy tanks and men, tanks and men go ashore and blow the hell out of the Krauts, who are already too busy dealing with the surprise-parcels dropped off thanks to the RAF and the Army Air Corps. The battle started with parachute-troops being dropped behind enemy lines. Their jobs were to secure important locations such as villages, roads and airfields. They were to link up and create a barrier so that reinforcements couldn’t get to the beaches as quickly as they might. Bombers would fly over the beaches and perform saturation-bombing of the coastline. This was to knock out as many enemy bunkers as possible, but also to provide some nice hidey-holes for the Allied troops when they came ashore.

The coastline of Normandy was divided into six specific beaches, all codenamed. In order, they were…

Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno and Sword, as seen on this map:

Once the airborne troops were dropped behind enemy lines, they went about their objectives, linking up and then spreading out in groups. They secured important roads, bridges and railroad lines. They also tried to disrupt enemy movements as much as possible, attacking German troops and sabotaging German artillery-positions, which were located further inland than other Allies could reach. By blowing up the German artillery-guns, the airborne units stopped shells being rained down on the beaches, giving their fellow fighters a chance at the enemy.

Not everything went perfectly, though. Omaha Beach especially, was a mess. The D-D tanks, deployed too far out in the ocean, sank before they could reach land. The aerial-bombardment had failed to knock the German machine-gun nests out of commission and the beach was as flat as a pancake when the soldiers arrived. With no shell-craters for them to take cover in, the Americans were sitting ducks for the Germans who machine-gunned them down in their hundreds. Omaha became known as “Bloody Omaha” after the war.

The Battle of Normandy started in the pre-dawn of the morning of the 6th of June, 1944. An allied armada, a naval and aerial taskforce the size of which the world had never seen before and which it has never seen again, charged towards the French coast after crossing the English Channel from a number of British seaports.

The objectives of the battle were to destroy German coastal defences, liberate France and establish a secure beach-head for the Allies so that extra troops and supplies could be driven and shipped onto the battlegrounds. The fighting, as depicted in films such as “The Longest Day” and “Saving Private Ryan” was fierce and prolonged. The Germans knew that the moment the Allies broke through their defences, they would come steamrolling in like the neighbours from hell, destroying everything in their path.

Once the Allies had destroyed the German defences and liberated some of the coastal villages, they were able to set up bases. Since no harbour (or at least, no harbour sufficient for warships) existed in Normandy, the Allies knew they would have to build one. Floating in huge pontoons, they were able to hastily construct a manmade breakwater and piers which led out deep enough into the English Channel for ships to dock and offload their cargos. Called “Operation Mulberry”, it was one of the most essential elements of the D-Day invasion. Without a port (even if it sounded like one you might buy from IKEA), the invasion would have ground to a halt. Once the beach-head was established, without a constant stream of supplies, men, ammunition, food, fuel and firearms, the invashion would have ground to a halt. All very imporant reasons for the creation of a floating harbours. With this vital entrance to Europe secured, the Allies could now push forward in their liberation of Europe. It was one of the most crucial battles of the Second World War. It meant that now, the Germans were fighting a war on two fronts (France and Russia) and this caused the German Army to split up its resources, meaning that the Allies would be able to beat them easier.

The Air-Battle for Normandy

Normandy was many things. It wasn’t just storming the beaches. It also wasn’t just an attack by ground-forces. It wasn’t just a naval assault. It was also a huge aerial pre-emptive strike by the Allies.

Knowing that they wouldn’t succeed at Normandy without dominance of the air, the Allies spent weeks in advance attacking German-occupied France using the combined power of the United States Army Air-Force and the Royal Air Force. Their objectives were to blow up bridges, destroy railway lines, attack aircraft factories and destroy every single airworthy flying-machine within attacking-distance of Normandy. They strafed and gunned and bombed airfields left, right and center, destroying hangars and airfields, runways and as many enemy planes as they could find. They also bombed the beaches that the landings were to take place on.

Raiding the beaches was an essential element of the air-assault on the north of France. Although the Allies knew that destroying the German machine-gun bunkers through carpet-bombing was going to be only marginally successful at best, bombing the beaches would have the advantage of giving their advancing ground-troops plenty of fox-holes in the sand in which to hide from enemy gunfire. Without this crucial attack on the beaches, the British, Canadian, American and Commonwealth troops storming the beaches would be sitting ducks for the Germans, who had mined, barricaded and wired every square inch of the Normandy coastline…at least, every square inch that wasn’t flat and smooth as a billiard table to serve as an unobstructed killing-field.

The End of the Battle

There are conflicting dates for the end of the Battle of Normandy and of Operation Overlord in general. The most accepted view is that it was the 25th of August, 1944, with the liberation of the French capital of Paris. After a battle that lasted six days, the Germans were finally overwhelmed by a mix of Free French forces, American infantry and French resistence fighters within the city and were forced to surrender. The fact that many of Paris’s historical buildings such as the Eiffel Tower, the Louvre Museum, the Arc D’Triomphe and the Cathedral of Notre Dame still survive today, is due wholly to the occupying Nazi governor’s decision to ignore Hitler’s famous command that Paris be razed to the ground to try and destroy Allied morale.