China has not had an easy history. In the last one hundred years, China has gone from a monarchy to a capitalist, democratic republic to a communist state. China has seen great changes and turmoils. It has seen wars, famine, revolution, disease, infighting and upheaval. But what do we think of when we think of Chinese history? We think of Emperors, Empresses, princes, princesses, big, fancy houses, fine furniture, paddyfields, baggy robes, pigtails, chopsticks, incense, Taoism and the millions of Chinese peasantry.

But what was China really like back when the Chinese Empire still existed?

China: A Land of Empire

China has had a long history of tens of thousands of years and over a dozen dynasties and smaller kingdoms ruling over it, all fighting for power and control. China is a massive country and controlling the entire nation is an ambitious undertaking. For centuries, kings, armies and emperors fought each other and at various points in Chinese history, the country was united, divided, united, divided, united and divided yet again, as kings, emperors and generals fought for control. To try and cover over four thousand years of Chinese history in one article is far too ambitious…so I won’t. Let’s take a more general view of Imperial China and look at the parts of China that have entered the public, global image of China.

The Chinese Emperor and the Mandate of Heaven

In older times, China was ruled by an emperor, as were most Asian countries, such as the current Emperor of Japan. In China, the Emperor was seen as a demigod, appointed by the Chinese gods to be their representative on earth. Think of it as the Chinese equivalent of the Western belief of the ‘Divine Right of Kings’.

The Emperor held absolute power over all of China (provided of course, it was all of China that he controlled at the time of his reign). His right to this power came from the ancient belief of the Mandate of Heaven, similar to the above concept of the Divine Right of Kings in Western monarchies. In its essence, the Mandate of Heaven, according to traditional Confucian teachings, stated that so long as an incumbent emperor was reasonable, kind, just and merciful towards the commoners, he would retain the right to rule. If his rule became objectionable in any way and remained so until it became intolerable, it was the right of the people to overthrow the emperor and his dynasty and establish a new one. If the emperor was successfully overthrown and defeated, the common people would take it as a sign that the emperor had displeased the gods and had therefore, lost their blessing and protection, which meant that the blessing of the gods would transfer to the next dynasty to be established.

And this was the essence of Chinese dynastic imperial rule for centuries.

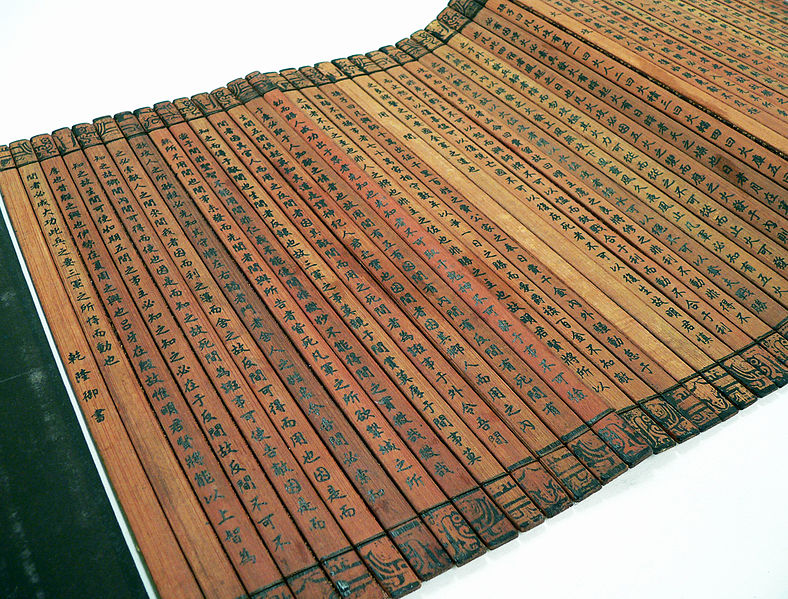

According to research of ancient Chinese documents, the Mandate of Heaven has existed ever since it was put to paper by Zhou Gongdan, brother to the first emperor of the Zhou Dynasty (established 1045 B.C). The original documents as written by Duke Zhou Gongdan, outline the eight main points of the traditional Mandate of Heaven, as was followed by every ruler of China since then for the next two thousand years. In essence, they state that:

1. The Right to Rule China is Granted by Heaven.

2. There will only be ONE ruler of China at any one time.

3. The right of the Emperor to Rule is based on his good conduct and his being the earthly representative of Heaven.

4. While the Mandate of Heaven is maintained, dynastic rule (father-to-son) is allowed. Failure to maintain the Mandate will result in the loss of the right to dynastic rule.

With these four main rules of the Mandate of Heaven came the four corresponding implications or conditions:

5. The ruling family of China must be seen as legitimate by the People of China.

6. If China is ruled by more than one family or person, the family or person that puts forward a legitimate claim to the Mandate must be able to justify it to the people of China.

7. Rulers are responsible for their own behaviour and must make the welfare of the Chinese people their first priority.

8. Rulers of China should always be mindful of revolutions. A revolution would indicate the displeasure of the people and therefore, the loss of the Mandate of Heaven.

If you read the Terms and Conditions of the Mandate of Heaven, you may notice that it doesn’t mention anything about noble birth. Noble birth is not (and never was) a condition of rulership over China, in contrast to rulership of contemporary Western monarchies. In theory, any man could become ruler of China. Of course, the men with the best chance of ruling China were those who were already close to the emperor, men like advisors, ministers and prominent royal officials.

The Imperial Examination

You might not believe it, but becoming part of the governing class of Imperial China was not as difficult as it might seem.

In ancient times, the only way to get into the Chinese Government was to ‘know the right people’.People gained access to the administrative bureaucracy by being recommended for vacancies by current bureaucrats or by prominent Chinese noblemen. Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty established an examination system during his reign (141 B.C. – 87 B.C.) based on Confucian teachings. Any man could apply for these examinations if he could pay the fees and had the necessary education. Applicants or students who passed the examinations would be given posts in the Imperial Bureaucracy. From there, it was just a matter of getting promoted until you got high enough in the imperial ladder to hopefully one day, become emperor. The Imperial Examination was a part of Chinese life until the fall of Imperial China centuries later.

The Forbidden City

The most famous (and the largest) remnant and symbol of Imperial China and the Chinese Emperor: The Forbidden City in Beijing, China.

Despite what you might think, the Forbidden City was not the first palace to house the Emperor of China. In fact, the Forbidden City was not built until the second emperor of the Ming Dynasty came along. The emperor’s father, the first emperor (and founder) of the Ming Dynasty moved the Chinese capital from Peking to Nanking (what are Beijing and Nanjing today) during his reign. When his son, the Yongle Emperor came to the throne, he moved the Chinese capital back to Beijing and in 1406, ordered the start of construction of a grand new imperial residence that would eventually become known as the ‘Zijincheng‘, or the ‘Purple Forbidden City’ (In China, as was also the case in contemperous Western monarchies, purple was the colour of monarchy. Why? Because purple dye was notoriously difficult to make, and therefore extremely expensive, which meant that only kings and emperors could afford it). In time, the structure just became known as the ‘Forbidden City’.

The Forbidden City took fifteen years to build. It holds the Guiness Record as being the largest palace complex on earth. From the completion of its construction until the fall of Imperial China, it was the seat of power for the Chinese Emperor.

The Forbidden City gets its name quite simply because commoners were forbidden to enter its walls. The only people allowed inside were the Emperor’s family, government officials, servants, courtiers and of course…the Imperial eunuchs.

Eunuchs have a long history in China. They ranged from prisoners of war to men found guilty of the crime of rape (or any other crime for which castration was the punishment) and men who became slaves were also turned into eunuchs. But most famously, eunuchs were employed in their thousands by the Imperial household to act as servants to the emperor and his family. Since eunuchs were incapable of having sex, they were unable to establish their own families (and by extension, their own dynasties) which might threaten the power and position of the emperor, which was the main justification behind the employment of eunuchs by the Imperial court.

The Peculiarities of the Palace

The imperial palace, the great Forbidden City in Beijing, was (and remains) unlike almost any other palace complex in the world. To begin with, it is the largest palace complex in the world. It has hundreds of buildings and miles of walls, dozens of watchtowers, acres of courtyards, gardens and several enormous gates. The walls and gates divided the palace and servants, courtiers, officials and members of the imperial family were strictly segregated. Only certain people were allowed in the innermost areas of the palace grounds and buildings where the emperor lived with his family. In total, the palace has 9,999 rooms. This was considered good luck because the Chinese word for ‘nine’, ‘Jiu‘, is pronounced the same way as the Chinese word meaning ‘long-lasting’.

Because a number of the buildings in the palace were made of wood, there are several enormous cauldrons placed around the various palace courtyards. The cauldrons were used to collect rainwater which would then be used to put out fires in an emergency.

Despite the palace’s enormous size, because it was also designed as a fortress, there are only four gates into the main complex, and a fifth gate (the Gate of Supreme Harmony) that leads to the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the structure used by the emperor on his wedding-day and on special occasions. Because of the hall’s general inaccessibility, it was impractical to use it on a regular basis when the emperor would hold court. So, although this was officially one of the hall’s intended purposes, it was rarely occupied for this use. The Hall of Supreme Harmony is also the location of the ‘Dragon Throne’ mentioned in the title of this article. The Dragon Throne was the official seat (literally) of the Emperor of China.

Colours play an important part in Chinese culture, and some colours held special significance in the Chinese Imperial Court.

Red was the colour of happiness.

Purple was officially the colour of the Emperor of China himself, although he might also wear robes that were dyed yellow instead.

Gold or Yellow was the colour of the Imperial Family. In imperial times, only members of the Imperial Family were allowed to wear yellow or own objects coloured in yellow.

An interesting fact is that the floor of the Hall of Supreme Harmony is laid with golden bricks to symbolise the Imperial Family and the emperor. Okay, that’s not quite right. Yes, the floor of the hall is made up of bricks. But no, they don’t actually contain any gold. They get their name ‘golden bricks’ because the bricks (fired in the imperial kiln), took an incredibly long time to make. Because they took so long and were so difficult to make, each brick was considered to be worth it’s weight in gold (and probably cost just as much!), hence the name ‘golden bricks’.

The Last Emperor

The Chinese Empire lasted for centuries. But it could not last forever. And it couldn’t last in the 20th century.

The Opium Wars and the Boxer Rebellion of the late 19th century caused great instability in China. The last dynasty, the Qing Dynasty, was becoming increasingly unpopular with ordinary Chinese citizens…probably because it wasn’t Chinese.

That’s right. A Chinese dynasty that wasn’t Chinese. How is this possible?

The Qing Dynasty just sounds so…Chinese…doesn’t it?

Well, that was the whole point. To make it sound as Chinese as possible. That way, hopefully, people would forget the dynasty’s other name: The Manchu Dynasty.

The Manchu Dynasty got its name from where its people originated from, a geographic region northeast of China, then called ‘Manchuria’. But how does this differ from the rest of China and how do its people differ from the rest of the Chinese population?

Well, up until the mid-1600s, China had always been ruled by a Han emperor. That is to say, it was ruled by an emperor who came from amongst the Han people, the Han being the main ethnic group in China (this is why the Chinese language is called ‘Hanyu‘ or the ‘Han Language’, and the Chinese people are called ‘Hanren‘ or the ‘Han People’ in their native tongue).

But in the early-1600s, all this changed and Manchu people from the north of what is now part of China, invaded Beijing. To the ordinary Chinese people, they saw the Manchus as being foreigners and not part of the China or the Chinese people which they knew. They were not Han people and were therefore considered outsiders. But the Han seized power in the 1640s and remained in power, founding the ‘Qing Dynasty’ to make themselves sound ‘more Chinese’.

The Chinese people, who had been growing more and more displeased with the Qing Dynasty, were itching for a chance to abolish the monarchy and found a new government: A western-stye democractic republic.

In 1908, the aged and extremely bad-tempered Empress Dowager, Cixi, died of old age. She had ruled China as it’s empress for nearly fifty years after the death of her husband. When she died at the age of 72, the last emperor of China inherited the throne.

He was not a powerful man. He was not an authoratative man.

He was not a man at all.

In fact he was a boy.

And his name was Puyi.

The diminutive Puyi, just three years old when he inherited the throne, was the great-nephew of the Empress Dowager Cixi (a fact that took me a while to figure out. Imperial Chinese succession can be hideously frustrating, confusing and convoluted). He ‘ruled’ from 1908-1912, although, because he was far too young at the time, his father ruled as his regent.

In 1912, the Republic of China was declared and Puyi abdicated in 1911. He was briefly restored to power for the grand total of eleven days in 1917, but was dethroned on the 12th of July, 1917 and lost power for the second time in less than ten years; this time for good.

Puyi lived in the Forbidden City with his family and his servants and courtiers until 1924. By now, Imperial Chinese Rule had disintergrated to such a level that it was little more than a show of power and a shadow of what it once was. The palace eunuchs had all been fired in 1923 and the enormous imperial complex was virtually empty. In 1924, Puyi was finally kicked out of the palace. To prevent his returning to the Forbidden City and possibly staging a coup to take back the throne, the entire palace complex was declared a museum and the Forbidden City was given its current name: the Palace Museum.

Puyi’s life was one of constant change. Even though he was an emperor of China, he never ever really ruled anything. Not China, not even the puppet-state of Manchukou which the Japanese made him the ruler of in 1932. He finally died on the 17th of October, 1967. He was 61 years old.

Before his death, Puyi was encouraged by the government of the People’s Republic of China to write his autobiography, perhaps recognising his significant and special place in Chinese history. His autobiography (translated from Chinese) is “The First Half of My Life“. When the text was translated into English, it was given the title “From Emperor to Citizen”.

The History of the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City (documentary)