Today, the car, the automobile, the horseless carriage and that stupid rust-bucket that’s parked in your garage right now, is as much a part of life today as is the television, the internet, the iPod, Phone, Pad and (regrettably) rap ‘music’. But spare a thought for the fact that motoring as we know it today is only a little over a hundred years old. It would be fair to say that the average man on the street wouldn’t know a single thing about the history of the very thing he’s driving around at that very moment: The motor-car. This article will be a brief peek into the history of the greatest thing since the steam-engine…

Before the Car

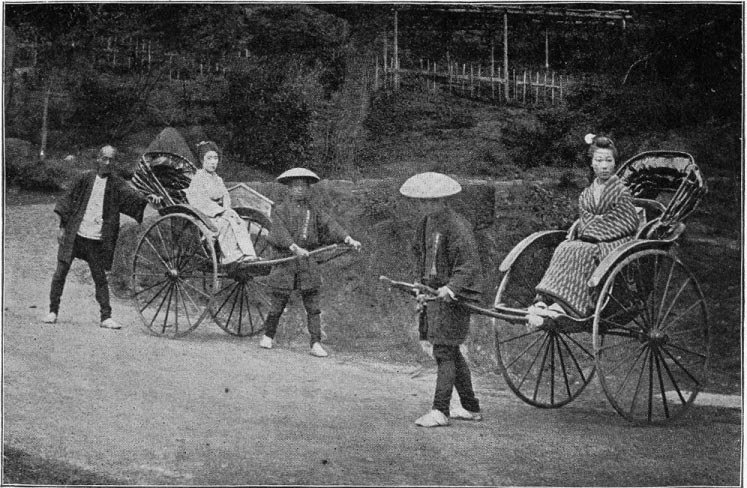

It’s hard to imagine life before the car, isn’t it? A world of steam-trains, ocean-liners and horses and carriages. A world where horsepower was literally horse-powered. If you didn’t own a horse and carriage of some kind, you were stuck with either walking, or taking a train or streetcar somewhere. While self-powered land-vehicles that could move on the road existed in the 19th century, it wouldn’t be until the early 1900s that they would become seriously practical. And it wouldn’t be for a few more years, that your regular Tommy Ryan could afford to buy one of these new horseless-carriage gizmoes out of his own pocket and drive it around town.

The Birth of the Motor Car

This…is genesis:

This here is the Benz Patent Motorwagen and it is quite literally, the first car ever made. It was powered by a two-stroke, one-horsepower engine and it was introduced into the world in 1885. Queen Victoria was still on the throne. Jack the Ripper was still sharpening his butterknife and Sherlock Holmes was still a blob of ink inside an inkwell. But this contraption, born in an age of the horse and buggy, was about to show everyone that personal, motorised transport was possible.

Although the Benz Motorwagen was hardly ideal as a car: It had no safety-features, it had three wheels, it had a tiller steering-handle and a pathetically small fuel-tank, not to mention a hopeless range of operation, Benz was not about to give up. Over the next few years, he refined and modified his machine to such an extent that in August of 1888, what was possibly the world’s first stolen car report was filed at the local police station (okay that’s a joke, it wasn’t, but you’ll soon see why it might’ve been). For on a day in August in ’88, Mrs. Bertha Benz, Karl Benz’s wife, successfully started her husband’s car and, with her two sons along for the ride, drove them off to visit their grandmother, before driving back home three days later. The length of the trip was 120 miles! Mrs. Benz had successfully shown the world that the car could travel long distances!

The Benz Motorwagen No. 3, made in 1888. This was the car which Karl Benz’s wife started up and drove off in, on that August day, over 120 years ago

Over the years, more and more people started experimenting with these newfangled “internal combustion engines”, in attempts to create their own ‘horseless carriages’ as they were still widely called. The British Government didn’t take kindly to scientific and technological advancement in the world of transport, however, because it slapped a FOUR MILE AN HOUR speed-limit on early motor-cars! The first speed-limit ever imposed for self-powered vehicles was 10mph in 1861. In 1865, the Brits made the law even tighter, saying that self-propelled vehicles could travel at the breakneck speed of four miles an hour in the country but only two miles an hour in town! Finally in the 1890s, though, with the arrival of the motor-car, British lawmakers allowed a speed-limit of 14 and later, 20 miles an hour, starting in 1896.

Car companies sprang up almost overnight as the 20th century approached. Some notable early ones included Renault (1899), Ford (1903), Mercedes (1902) and Stanley (also 1902), which was famous for making steam-powered motor-cars. Slowly, the world took to the road.

Starting Something Totally New…

- “…For making the carriage walking at the first speed, take back the drag of the wheel backward crowbar of the right and take completely and progressively back, the crowbar of embriage…”

– Jeremy Clarkson, “TopGear”.

Okay, I kid, I kid…that’s actually French translated into English. But as you can see, early motor-cars were far from easy to drive. These days, we get in, we insert the key, we turn it, we swear for a couple of minutes and then we get moving. Early cars were nowhere near as easy to operate. To start with (literally), you had to crank these cars to get them going.

Early cars did not have ignition keys, they didn’t have electric starter-buttons, starter-motors or anything like that. To get them going, you had to crank them by hand. And while this looks like a lot of fun, it wasn’t exactly easy. You’ve probably seen vintage cars in movies or cartoons being the subject of slapstick comedy where someone tries (hopelessly) to get a car started by cranking it, only to fail miserably. The truth is that some (but not all) early cars were that hard to start. And not only hard to start, but also dangerous! You needed considerable strength to start a car in the old days, because everything inside the car was mechanical and made of metal. If you didn’t have the muscles to turn the crank-handle (which could be particularly tricky in some cars), then the car never started. Usually, you slid the crank-handle into a hole in the front of the car, which sent the crank through the crankshaft inside the engine. Then, you grabbed the crank and with considerable force, turned it clockwise in an attempt to get the pistons moving to start the engine-cycle.

One of the big risks of crank-starting a car was personal injury. By cranking the starting-handle, you moved the crankshaft inside the motor and this got the pistons inside the engine moving. Once the sparking-plugs ignited the fuel and the engine started working by itself, the car could be driven. But when this happened, one of the biggest risks was of the crank-handle being thrown backwards, against the driver’s hand, by the force of the pistons coming to life. The most common injuries included broken wrists and broken arms. Nasty stuff! Several early motor-car companies tried to introduce braces or catches or modified engines where the starting-handle either jammed or was stopped in some way, if the engine backfired, or else disengaged the starting-handle when the engine caught on, so that it wouldn’t kick back and break the driver’s arm.

A 1909 Model T Ford with prerequisite antique car crank-handle at the front. Apparently this one disproved that a motorist could have his car any colour so long as it was black

Early motorists were instructed to grasp the crank-handle in a certain way, with all fingers on ONE side of the crank, instead of four fingers on one side, and the thumb on the other (as you might do with other crank-handled appliances). The reason for this, was so that if the engine kicked back, the handle would swing away from your hand and nothing went wrong. Grasping the handle the traditional way meant that at the very least, you suffered a broken thumb when the engine came to life. The increasing power and size of car-engines as the 1900s progressed, meant that it began to take more and more strength to crank start a car and eventually, electric starter-motors were introduced.

Of course, not everything was this easy. Headlamps on the earliest cars were gas-powered. These had to be lit either manually, or with pilot-lights or sparkers. And starting a steam-powered car, such as those manufactured by the Stanley company up until 1925, was almost like trying to get a steam locomotive going from a cold start. First you had to fill up the boiler with water, and then you had to make sure that there was enough kerosene in the tank, you had make sure that the pilot-light was on and that the water was being boiled sufficiently. With the water boiled, you had to wait for the steam-pressure to build up before you could actually drive the car away. Considering how tricky it was to get a steam car started, it’s rather surprising how long they survived. The reasons for building steam cars, however, was rather obvious when you consider that the steam-engine had been around for about a hundred years longer, starting in 1900, than the internal-combustion engine, the bit of machinery that drives almost every car in existence today.

Driving Along in my Automobile

Early motoring was a thrill. It really was. These days, we use a car for everything. Going to school, going to work, going to the shops, going to visit friends and family…but things were very different a hundred years ago when you were probably the only person on the block who owned his own motor-car! Having got the car started, you didn’t want to just waste all that petrol and water and oil driving somewhere for a PURPOSE, did you?

No! Once you got that thing going, you wanted to muck around with it, yeah? Which is exactly what many people did. Having a family car in the 1900s or the 1910s was considered a real luxury, and many of the times that the car drove off down the road would have been with the entire family onboard for a roadtrip or an excursion. Barrelling along at twenty or thirty miles an hour was a thrilling experience when you consider that the other way to move around was by horse and cart.

However, taking the family out for a spin in your new automobile wasn’t always safe. Most early roads were almost lethal to drive on. They were mostly dirt roads or cobblestone or flagstone roads, which gave no joys to the passengers in your shiny new ride when suspension hadn’t really been thought of yet. And even if you found a nice road to drive on, when you parked your car, you had to make sure that nobody tried to pinch it! Henry Ford used to have to chain his car to a lamppost everytime he parked it and secure it there with a padlock, otherwise, the moment he stepped away, some inquisitive bystander would try and crank up his new toy and drive off with it!

However, getting to treat the family to a ride in the automobile was something that was nothing but a dream, and for many men, remained a dream until 1908.

Model T Fords and Mass-Production

One of the biggest problems of early motor-cars was the fact that they were dizzyingly expensive. A car in the 1900s could cost upwards of $1,000. While this doesn’t sound too bad today, remember that in 1900, a good pocket watch cost $50, a fountain pen cost $2, a film-ticket was five cents and it was cheaper to send a telegram than to use the telephone! Groceries for a family of four for a week could be bought for less than $20!

Because of the dazzling cars and the equally dazzling price-tags, it’s not surprising that for many people, motor-cars were something to be seen driving by, but never to be seen driving in. Cars were handmade with expensive coachworks which were made up of leather and brass and chrome and other fancy-schmancy things that cost a fortune. Only the richest of the rich could afford cars. Millionaires, businessmen, royalty, heads of state and so-on. For everyone else, the only rubber that was going to hit the road for them was the soles of their shoes.

That was until Henry Ford put two and two together and made Ford. Or the Ford Model T, to be precise.

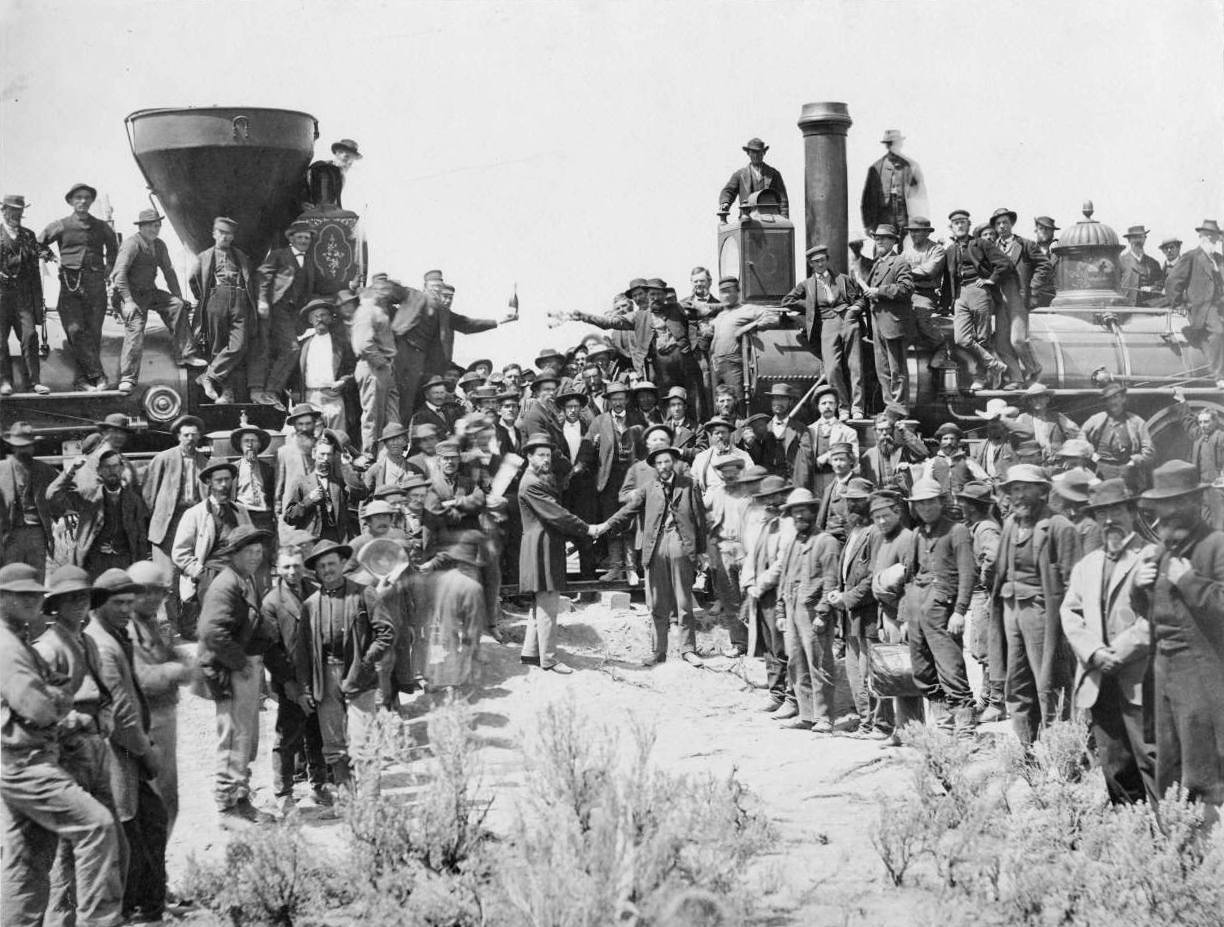

Henry Ford didn’t invent the car. He didn’t even invent mass-production. But what he did invent was a way to put the two things together. By working on a moving production-line, Ford realised that, with work coming to his men, instead of his men going to their work, a lot of time could be saved in manufacturing a car. One reason why cars were so damned expensive was because they took literally days, weeks, in some cases, even MONTHS to make. Not just a line of cars, I mean literally ONE car. If Henry Ford could cut down how long it took to make cars, then he could make more cars in a shorter amount of time. More cars meant that the prices went down and if the prices went down, then ordinary people could buy them.

The Model T was introduced in 1908, when Ford started mass-producing cars. The chassis, the wheels, the seats, the engine and everything else was built at one part of the factory and progressively joined together. At the end of the line, the body of the car was dumped on top. The final touches were added, the car was gassed up, cranked up and then driven off into the world. It was amazingly simple.

One reason that Ford managed to make his car plants so efficient was that he kept breaking down jobs. If making an entire door was too hard for one workman to do by himself, then Ford broke the door down into component parts. One man made the hinges, one man painted the panels, one man screwed on the doorhandles and one man put in the window. It meant that the Ford car plants had to employ hundreds, thousands of people, but it also meant that they could work for longer hours. Ford workers worked eight-hour shifts and earnt $5 a day. $5 a day when Cocoa Cola cost 5c, was a lot of money. And by having eight-hour shifts, the factories could operate literally around the clock.

This Ford Model T four-door tourer was typical of the millions of Model Ts produced by Ford: Simple, tough, reliable and understated

When Ford Model Ts were being sold, they originally started out at $850-950 (in 1908 dollars). If this sounds steep, then you can try and find something else for $900. Not easy when the next least expensive car skyrocketed upwards to $3,000!! As Fords continued to be made, however, the price did (thankfully) drop, to about $280 in the 1920s, which which time literally half the cars in the world were Model T Fords.

The Model T wasn’t a great car. It wasn’t fast (45mph top speed), it wasn’t classy (“a customer can have a car painted any color he wants, as long as it’s black”, Henry Ford), it wasn’t easy to operate (“…it’s more complicated than doing eye-surgery!…”, thank you Jeremy Clarkson) and it certainly wasn’t big (one of its nicknames was the ‘Tin Lizzie’! and you can be sure that doesn’t sound very chunky!), but what it was, was a car that allowed everyone from Dr. Jones right down to Mr. Bentley at the corner shop, to drive around town.

Changing the World, One Car at a Time

Everyone generally assumes that a car built before a certain time is either “classic”, “vintage”, “veteran”, “crap” or some other delightful categorical name. But what is what?

“Veteran” cars signify any cars made between the 1880s up to 1919. These include the very first cars ever made by most companies, and the earliest Model T Fords.

“Brass-Era” cars are cars manufactured in the period between Veteran and Vintage, generally accepted as been between 1905-1914/15. So named because of the heavy use of brass on these cars (headlamps, grilles, dashboards, side-mirrors, etc).

“Vintage” cars were cars manufactured from after the end of WWI to the Wall Street Crash, so, from 1919-1929. It was during this period that cars stopped looking like ghost-carriages without horses at the front, and started representing what we would sort of recognise as a car today, with a passenger area, the engine out the front with a bonnet or hood, four wheels and a roof and windows! It was during this time that cars also started being widely manufactured with self-starters; everything from electric starter-buttons to…*gasp*…car-keys!! Yes! No more broken wrists!

A 1929 Model A Ford, a typical vintage car of the 1920s and 30s, with curved mudguards and a less angular body, but boxy in appearance nonetheless

1916 Cadillac Type 53. Yes, that’s James May and Jeremy Clarkson from TopGear in the front, with Clarkson at the wheel. I think I’ll walk

According to the automotive TV show “TopGear”, it was the Cadillac Type 53 that gave us one of the greatest pieces of metal in the world. The car-key! With that, cars became safer, easier to start and more fun to drive. This template for the modern car was introduced to the rest of the world thanks to Herbert Austin, founder of the Austin Motor Company. The first car other than the Caddy Type 53 to have car-keys and all the gears and pedals in the configuration that we know today was the famous and miniscule Austin 7…

1922 Austin 7 “Chummy” Tourer

As you can see, the Austin 7, while ‘modern’ in the sense that it had all the controls in the right order, was hardly luxurious or any of that rot. It was basically an updated, more modern and British version of the Model T Ford. In fact the Austin 7 was so incredibly small, it was popularly nicknamed the “Baby Austin”. If you think you recognise the Austin 7 ‘Chummy’ Tourer, it’s because a 1/2-scale fully-functional model of the car (in bright yellow!) is used in the popular British TV series “Brum”.

Last but not least, we have “Classic” cars. For a car to be a ‘Classic’ car, it has to have been built between 1930-1960. Such ‘Classics’ might have included several cars manufactured by the famous “Deusenberg” company, the Chevrolet Bel Air, the Auburn Boattail Speedster and countless other wonderful machines.

As cars became more and more popular and companies started producing luxury as well as cheap models, the car began to take over the world, but the world wasn’t quite ready for it. Many roads were still unpaved and hideously dangerous to drive on. Ironically, when we think of early motor-cars, we think of them as delicate little sardine cans held together with chicken-wire which fell apart if you farted too loud, but actually, some of them were rather tough. The Model T Ford was able to start in almost any weather, it could drive through water, through snow, through mud, through dirt roads, up and down hills, it could literally drive off-road without breaking down and it did all this with a top speed of just forty five miles an hour and wooden-spoked wheels! It might’ve looked flimsy, but on the other hand, it might also have given the Jeep a run for its money.

And yet, the horse and cart still hung around. The last horse-drawn taxi-license was issued in London in the late 1920s. Police-forces did not start using regular patrol-cars until the 1920s and in some places, horse-drawn tram-services continued well into the 30s and 40s (although in all fairness, horse-tram services returned to some countries in the 40s because they needed the petrol to fight the Axis. You can’t use horse-poop for anything in warfare).

By the 1920s and 30s, the era of motoring had really taken off. The road-trip became a popular kind of holiday as families and their friends packed up their Packards, Studebakers, Austins, Fords and Maxwells (Hello, Jack Benny!) and took to the road. Petrol-stations, diners, roadside inns and caravans popped up almost overnight as cars started driving around the world. Cars gradually became safer as shatterproof glass began to replace the brittle glass that was previously used in windscreens and windows. In 1903, French chemist Edouard Benedictus dropped a glass flask which had the leftovers of cellulous nitrate plastic inside it. His happy accident led to his development of what we now know today as laminated or shatterproof glass. Not originally used in motor-cars, it would be another thirty years before this newer, stronger, safer type of glass replaced the dangerous and brittle glass then used in car-manufacturing.

The birth and development of the car was going along nicely until a small hiccup called the Second World War came along in 1939. Because of the strain of total war, car-production ceased the world-over, starting in 1940 in the UK and in 1942 in the USA, with no new cars being produced by either of those two countries (or indeed, several other countries) until 1945 at the very earliest.

Postwar cars were just as fascinating as their prewar parents and the boom years of the 1950s saw larger, chunkier cars being produced, such as one of the most iconic cars of the 1950s, the Chevrolet Bel Air:

The Chevy Bel Air symbolised cars of the 50s: Large, bold, excessive bodywork with more fins than a seafood restaurant and so much chrome that the car was basically a massive mirror on wheels. To its credit, though, the chrome-plating did have a practical use: It prevented the car from rusting from exposure to moisture.

From its humble beginnings as the crazy invention of a German engineering and metalworks student to one of the most important modes of transport in the modern world, the car changed everything around it, everyone in it, and everything that it drove past, forever.